2024

Countries visited: five

States visited: three

Plane flights: twenty

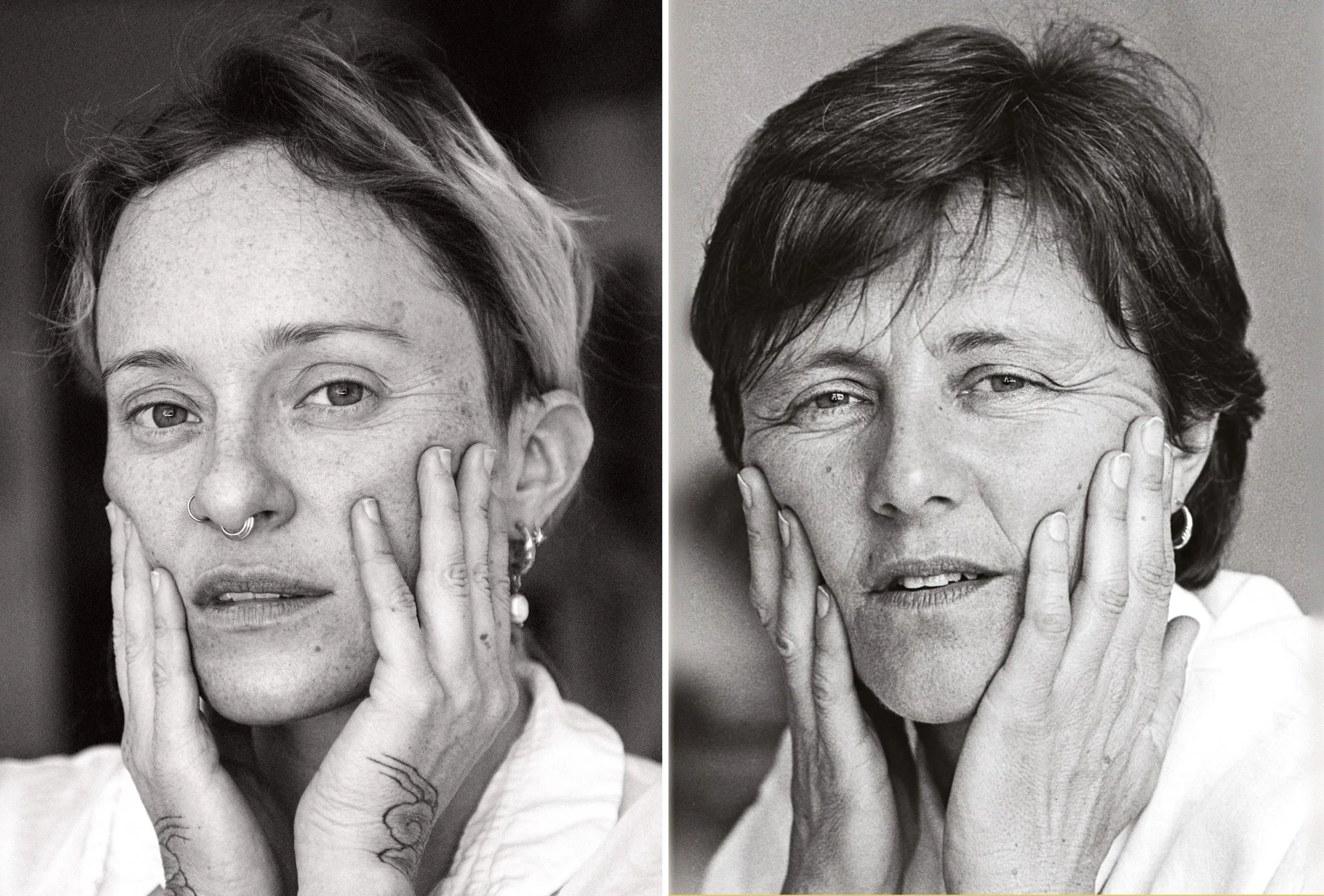

Most-liked photo on social media: this one, of me apeing Helen Garner’s portrait on the cover of ‘Yellow Notebook.’

New tattoos: six

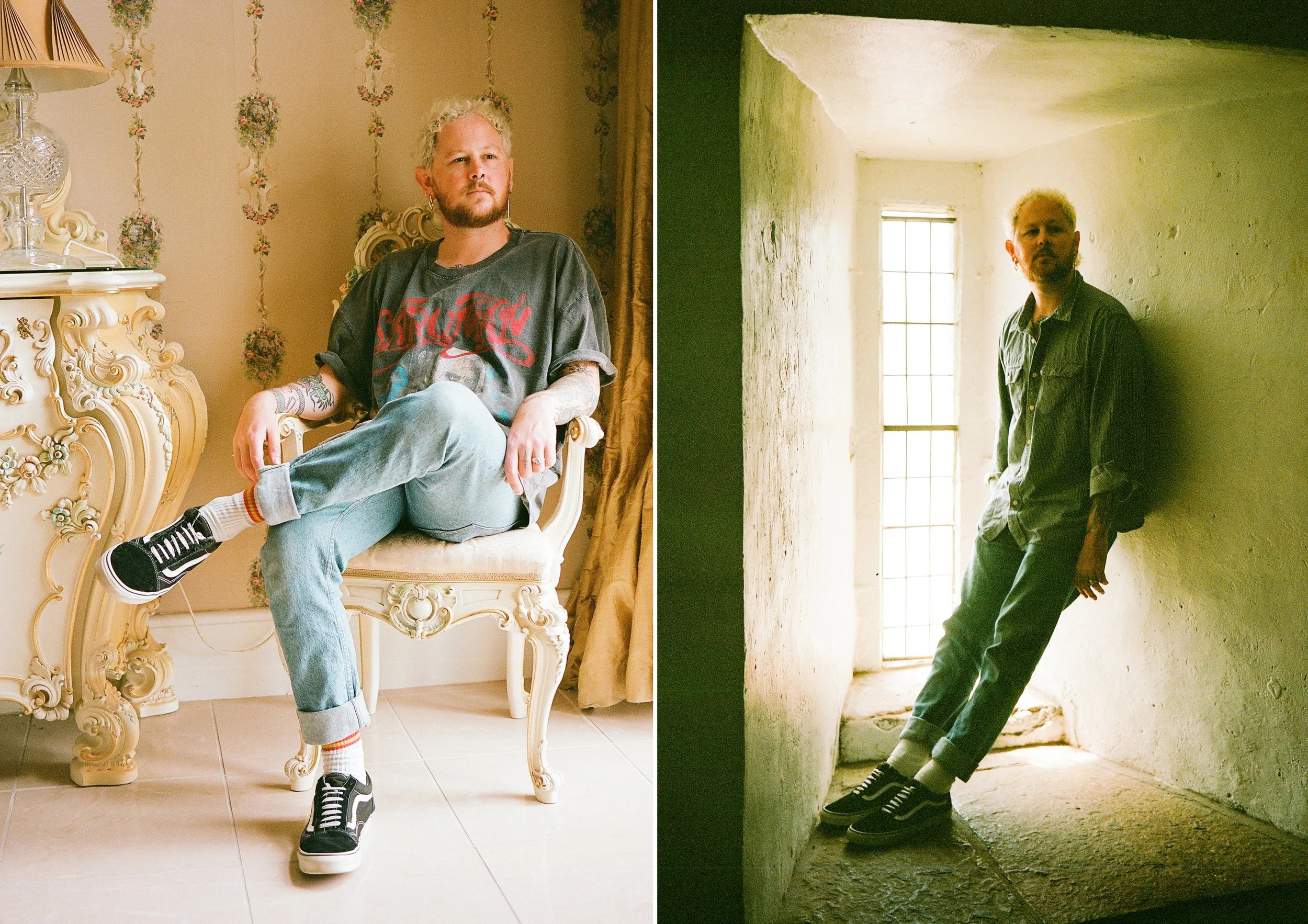

Favourite photo I took: this one, of three Irish boys intently watching a sword-fighting tournament at Bunratty Castle.

Most played song: ‘Fireball Whiskey’ by Angie McMahon.

Number of books read: 43

Of which, the best: ‘The Bee Sting’ by Paul Murray, ‘Anam’ by André Dao.

Best journal edition read: Granta 37: The Family.

Best films I saw: ‘Hundreds of Beavers’, ‘Kneecap’.

Best TV show I watched: ‘Deadloch’.

Best podcast I listened to: ‘Search Engine’.

Best pieces of theatre I saw: ‘The Crying Room: Exhumed’ (Marcus McKenzie), ‘Cuddle’ (Harrison Ritchie-Jones), ‘Refused Classification’ (Zachary Ruane and Alexei Toliopoulos).

Best exhibitions I saw: Tacita Dean at the MCA, Louise Bourgeois at the Art Gallery of NSW, Laure Prouvost at ACCA, the Bulgarian Pavilion at the Venice Biennale, Pierre Huyghe at the Punta della Dogana.

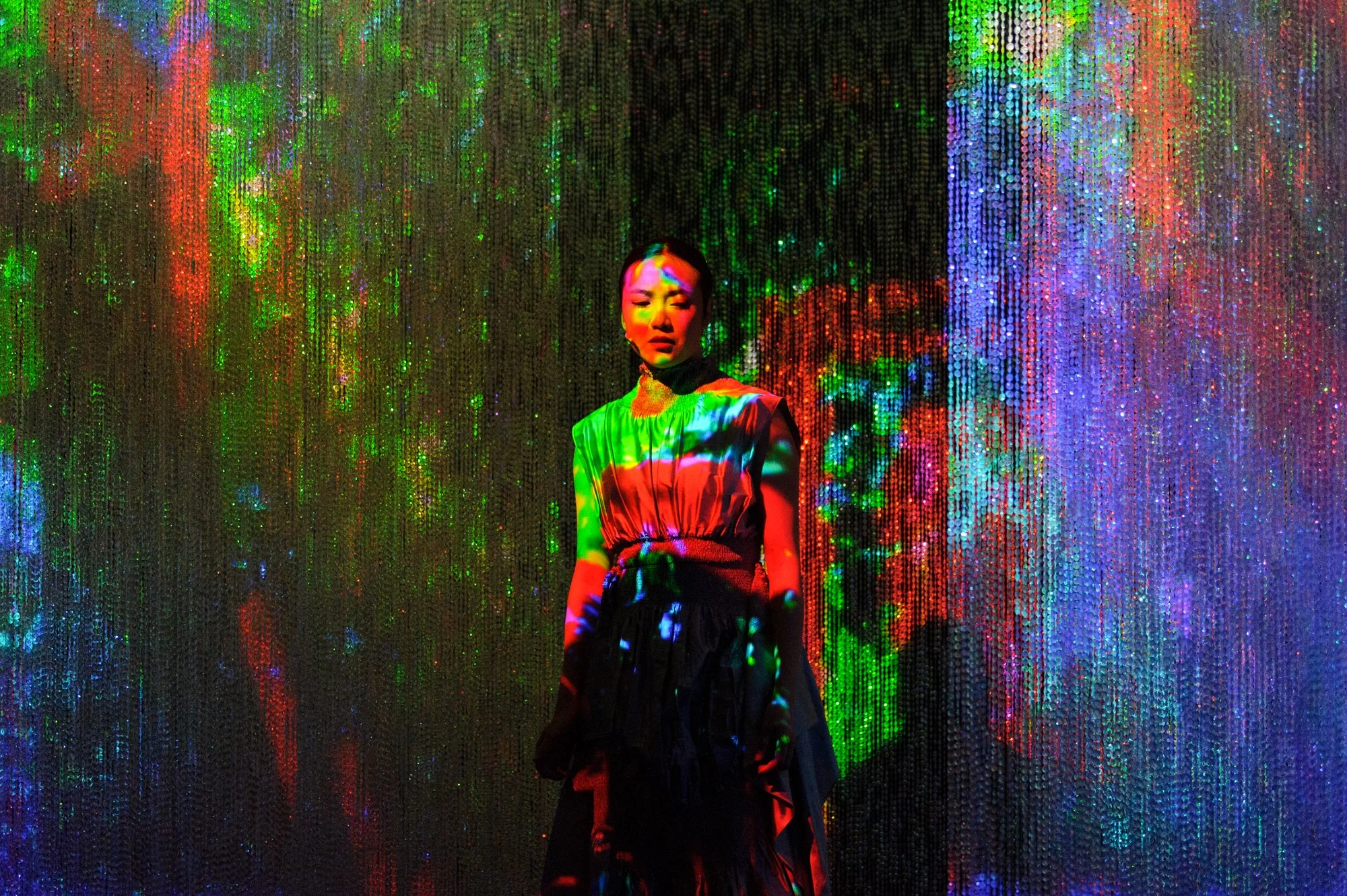

Shows I most enjoyed shooting: ‘ANITO’ (Justin Shoulder), ‘A Splendid Anomaly’ (Ahmarnya Price), rehearsals for ‘Cost of Living’ (MTC).

Favourite images I shot for work: these ones, behind the scenes portraits of Matthew Cassar for Tina Stefanou’s new work.

Submissions (including writing and art prizes, open calls, grants, calls for papers, residencies and labs): 23

Of which, successful: 2

Hair colours: seven

Weight fluctuation: three kilograms

Days on which I exercised: 185

Weddings: one

Funerals: one

Decisions I deeply regret: two

People I had sex dreams about: six

Dreams in which my mother was alive again, and I tried to convince her that she was actually dead: six

Dreams in which my mother was alive again, and we sat together quietly: one

Most articulate friend award 2024: Lewis Gittus

New phrase I particularly liked: ‘emotional sobriety’, via Bob Jarvis.

Ring designs I drew in notebooks: 46

Number of emails in my inbox that contained the word ‘sorry’: 295

Women I used to know who are now deep in the MLM wormhole, selling scammy water filters: three

Days on which my hair sorted its shit out and actually looked good: three

Days on which I wore lipstick: twelve

Interactive 3D scans made of my body: two

Projects complicated by Israel-aligned funding: two

Deeply discouraging public works in progress: one

Silliest thing I did for my PhD: filmed myself fully clothed in a sauna for 30 minutes, slowly getting more and more sweaty.

Last year’s new year’s resolution:

Get in the slipstream.

This year’s new year’s resolution:

Whenever possible, be this dog:

Defining word for 2025: pleasure

Moments that stand out:

January

I book in for my first ever facial, and while it is terribly expensive, the care with which the woman washes my feet and then wraps them in a warm towel makes me feel almost holy.

Mike and I go to Half Moon Bay and swim out to the half-sunken warship. We heave ourselves up over metal flaking rust and peer into the drowned interior. Two men stand by as a woman tries to pull herself up onto the deck, but she’s not strong enough. The men try to yank her up by her hands, but she falls back into the water, gasping.

At the Ronald McDonald House, a family have just lost their youngest child. Their eldest, a three-year-old girl, is on her way back to the house to be looked after by family while her parents grieve. She has become particularly attached to a plastic cash register which has jammed. I spend half an hour trying to fix it with a screwdriver and a set of pliers. I have to bring it to her and explain that I can’t repair it, that it’s still broken, that I’m sorry.

In the kitchen at dad’s place, he wanders in as I’m cooking. In perfect sync, we both lift our hands in a thumbs up, then burst out laughing.

We drive to Adelaide to stay with Mikey and Sarah. Mike swims at Aldinga Beach and emerges from the water covered in angry red weals like spears on his shoulders; the result of a bluebottle sting. We spend a drunken night at Nick and Stella’s, belting out torch songs. ‘The thing about a fire,’ Nick says, ‘is that it’s always dying.’

February

Art Camp. Anna and Andrea stand knee-deep in the ocean, using huge strands of seaweed as whips, smacking the water, cackling.

As I walk the dog, I see a small, black bug dragging a dead huntsman by the face, and immediately afterwards, a lowered, black hearse drives past with the numberplate NECRO.

We see Private Function at the Night Cat. A man climbs along the lighting rig. A security guard elbows his way into the mosh pit to try to collar him, but is blocked by a wall of grinning, sweating punters.

I water the garden at night, by the glow of the fairy lights Mike has installed. A great, fat praying mantis waves its arms in the stream of water.

March

Eleanor tells me that on first meeting, my enthusiasm seems too extreme to not be affected, but that it quickly becomes apparent that it’s real.

I fly over to shoot Fleur’s play, made with a group of teens. Afterwards, the performers stand outside and talk about their lives. They use the word ‘trauma’ liberally. They seem to not have any coping strategies for stressful situations in their lives, beyond leaving, cutting ties completely.

I ask my uncle to take me for a motorbike ride. He tells me to hold on to the handles alongside my hips, but the second we speed up, I lurch forward and wrap my arms around his chest. On the freeway, I tremble, terrified, but once we are up in the hills and winding down long roads through bush, it is beautiful.

Evie and Louis hurl themselves into our arms after dinner, yelling, ‘We love you! Kiss kiss!’

April

Mike comes home and reports that the vet took a sample of the lump in Jacko’s neck, and said, ‘it looks like a needle full of Crisco.’

At our RMIT PhD Monthly Club, a juicy conversation takes hold about practice and theory. Ming says, ‘this is what I imagined uni being like!’

Luna, idly: ‘I’m terrified that I’m accidentally going to eat one of my Airpods.’

At Frame Lab, Ros and I get lost at Werribee Mansion and climb a fence together. Later, we come out of an online session with an overseas mentor feeling disheartened. We sit in the hotel spa with the rest of the cohort. ‘Did anyone else find him…’ ‘Incredibly pretentious?’, someone asks, and this unlocks a great rush of laughter and relief from us all.

I return from the weekend residency. Mike hugs me. ‘I’m so lost whenever you go away,’ he says. ‘So much of me is you.’

A text from Sarah: ‘As I drove into town, a flock of galahs came and surrounded the car, flying at eye height. I had to pull over and cry.’

May

Dark days.

In a bar, a union representative tells me the key to union email copywriting when you’re asking for money: anger, then hope, then action.

Mike and I arrive at our accommodation in Bali late at night. The first thing we manage to do is lock ourselves on the balcony. I climb over and rap on the neighbouring balcony door. A groggy, frightened woman stands at the glass as I gesture, asking to be let in. I stumble through her dim room into the corridor and find Mike, who has managed to force the door after all.

We float in choppy water that tastes of diesel, trying not to bump into dozens of other people, as manta rays soar beneath us, like a visitation from angels, aliens, gods.

Sally reads my extant PhD chapters and says, ‘I think you need to write with more authority about your own work. I think you should consider post your PhD. You could become an expert in the field of art and anxiety.’

Mike and I walk through the darkened house with a lit candle, casting a spell.

June

My doctor photographs a mole on my temple with a tiny camera, accidentally brushing my eyelashes as his hands pass.

I am sitting in a restaurant courtyard in Venice, drinking wine. A man throws open the window of a third-floor apartment opposite, looks out for a moment, then buries his head in his hands.

Outside another Venetian restaurant, drinking more wine. A pride march goes through the town. The young people are so at ease in their queerness, wearing it like glitter. The older folks hold themselves upright, self-aware in an entirely different way. It makes me want to cry.

On the train to Milan, an American couple are in the wrong carriage. An Indian family arrive to take their seats, and some consternation ensues. The father leaves the youngest daughter with me, saying, ‘You stay here with auntie.’ The girl chatters away about her trip. She is from Calcutta, and her favourite thing about her trip has been seeing snow.

Dublin has changed since I was last here. The streets are full of staggering men who look as though they’ve just been punched in the face. But then we go to a storytelling event, and a woman weaves with word and song, and there is magic, still.

We arrive at Fourmagnac. I fall asleep under the branches of the walnut tree. The only sounds are bees, birds, cows.

July

In Coles, ‘You’re the Voice’ comes on the radio. A man walking down the aisle plays the drum break on the handle of his trolley.

A perfect winter’s night. Mike is out, so I sit on the sofa by candlelight with a blanket, a book and Alice Coltrane playing.

My novel is rejected by my publisher.

A man on the tram is arcing up at some Asian students. I start talking to him, to redirect his racism and anger. He is 66, Croatian. He tells me about his sons, who his wife says aren’t his. He asks if I have a good man. I say yes. ‘You must marry him,’ he says.

August

At Dani’s birthday, I notice that one of their friends has a pregnancy test in his back pocket. I ask him about it. He is shy. ‘Oh,’ he says, ‘my partner’s period is a bit late. We thought, maybe…’ A few minutes later, the two of them walk out of the toilet with wide eyes. ‘Are you—?’ He nods. The news flutters through the house, and we are all beaming, congratulating them.

At Queer Powerpoint, one of the speakers talks of chosen ancestors, about artists who we feel a deep connection with. I write down mine: Patti Smith, David Lynch, Maggie Nelson, Helen Garner, Walt Whitman, Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Italo Calvino.

The local ice rink lets me shoot some PhD footage. While I’m changing into skates, the man behind the counter tells us about a parent who skated over the hand of their fallen child, severing fingers. Blood on the ice.

After six months of collaborating, Ros says to me, ‘Ah, I’ve figured it out! You’re the dramaturg!’ I am delighted by this.

September

Rach, my agent, calls me. A different publisher has made a pre-empt offer for my novel. The amount is so outrageous that I scream.

Jess tells me that when she gave birth to Maddie, she was cradling her when she felt a great mass of excess flesh between the baby’s legs. She was scared, worried that something was terribly wrong. It turns out that the epidural had numbed her to the extent that she didn’t realise she was touching her own stomach.

Fleur, so at ease in early parenting. She makes pancakes for breakfast, and when Atty cries, she says to him: ‘Thanks for that excellent and clear communication.’ We go to a baby shower for her friend. I am exhausted, but nearly everyone there is queer and neurodiverse, and the conversation flows like water.

Mark and I stand sidestage at Hamer Hall, laughing at where our lives have taken us.

A new friend is over for dinner. ‘You know,’ he says to me, ‘I had a bit of an intimacy hangover after our last catch-up. I’m used to being the one that people tell everything to. It’s strange to be on the other end.’ Mike nods. ‘Sarah’ll do that,’ he says.

Mike has noticed that I never push the dining chairs in after I’ve left the table. He describes tidying the house earlier in the week, and thinking, ‘I want to spend the rest of my life pushing in chairs when that woman has left the room.’

October

Ash’s fingers tremble, ever so slightly, the whole time he is onstage.

Mike is in LA, and I am exhausted, exhausted, exhausted.

On Gertrude Street, the rider in front of me fails to move when the lights go green. I swerve to avoid him, and my bike tyres catch in the tram tracks. I go down hard on my side, and when I stand up, my foot is bleeding. At the Urgent Care, the doctor tells me stories about previous patients and sends me home with a scalpel to cut the stitches, as long as I promise that I’ll get Jess to do it; that I won’t do it myself. A vast bruise blooms on my thigh.

I install a work in progress version of my PhD work at part of the RMIT symposium. I have great conversations with staff and colleagues about it, but the official session is discouraging. The academic providing feedback asks, ‘Why are you making everyone look at you?’, and says that ‘performing anxiety is a white, Western privilege,’ then suggests that I should be making work about white fragility. The frustration of the work not being approached on its own terms.

At a climactic moment in the DnD game I run for six-year-old Maddie, I present her with a pendant that I have hand-made in silver. She looks at it idly, then drops it into her pencil case and asks what happens next in the game.

November

I have breakfast at a beachside café. A little bird comes and lands on my table. I feed it a crumb of banana bread. The waitress sails past. ‘That’s Steve,’ she says. ‘We fed him as a baby and now he hangs around all the time.’ Steve hops forward and spears his beak into my dish of leftover butter, leaving neat parallel strokes, as though the tines of a fork have been dragged through it.

Aaron tries on the wedding ring I have made for him. It fits perfectly. He gazes at it, turns his hand this way and that. His fiancée texts me later, to tell me that he hasn’t taken it off since.

Carla, Annie and I sit and plan Carla’s death café event. Lady, one of Annie’s adopted disabled dogs, drags her paralysed back feet over for a pat. I help Annie change her nappy on a specially designed table.

My grandmother is dying and I am on a mountain, my lips pressed to a tree. My aunt texts about her death-rattle, and I strip bark from the trunk, like peeling skin off sunburn. My grandmother is dying, and I run past a huge, black snake and a darting brown rabbit. My grandmother is dying and a sinkhole has opened in the road so I can’t go down the mountain to get my car. My grandmother is dead, and I am being driven to a train, and I get an email saying I have been granted a three-month writing residency in Paris at the end of next year.

In the café courtyard, Jacko lunges suddenly into the bushes. There is an aggrieved squeak, and when Jacko lifts his head, blood is dripping from his nose. The blood is his own.

December

A monk spends six hours making a sand mandala at Carla’s Expiry D8 event. He chants with a deep voice, and then calls people up to destroy all the work. Outside, a man is sitting, swaying, terribly drunk. I start talking to him. He is sweet, embarrassed, sensing that this moment is a turning point for him. We talk about his family, about workplace socialisation, about Melbourne warehouse raves in the 90s. I try to get him into an Uber, but he can’t seem to collect himself, so I drive him home, and the whole way, he asks, ‘Why are you doing this? Why are you being so kind? People aren’t this kind!’ ‘Well,’ I say, ‘I guess I’m your guardian angel.’

At a bar, a friend tells me about his suicide attempt. I hadn’t known.

My choir performs at Hamer Hall. I stand next to a woman called Helen, and we grin every time we get one of the lyrics wrong.

On the train home, a man scribbles a tag on the window in thick, rich yellow paint marker. He turns to see me watching. ‘Product of a troubled upbringing,’ he says.

Pen, Tanya and I go to a carols service at St Michael’s. The choir sings ‘O Holy Night.’ When the arrangement opens up on the line ‘fall on your knees’, I burst into tears. Pen and I sing harmonies during the group hymns. After the service, the woman behind us says, ‘It was lovely being near you. I really liked your energy.’

Mike, Mikey and I run through the hot streets, singing ‘Sixteen Tonnes.’ We come out onto perfect white sand dunes, and run into perfectly blue water. Mike pulls me towards him by my legs and kisses me, sunscreen and salt.

S x