2023

States visited: three

Plane flights: nine

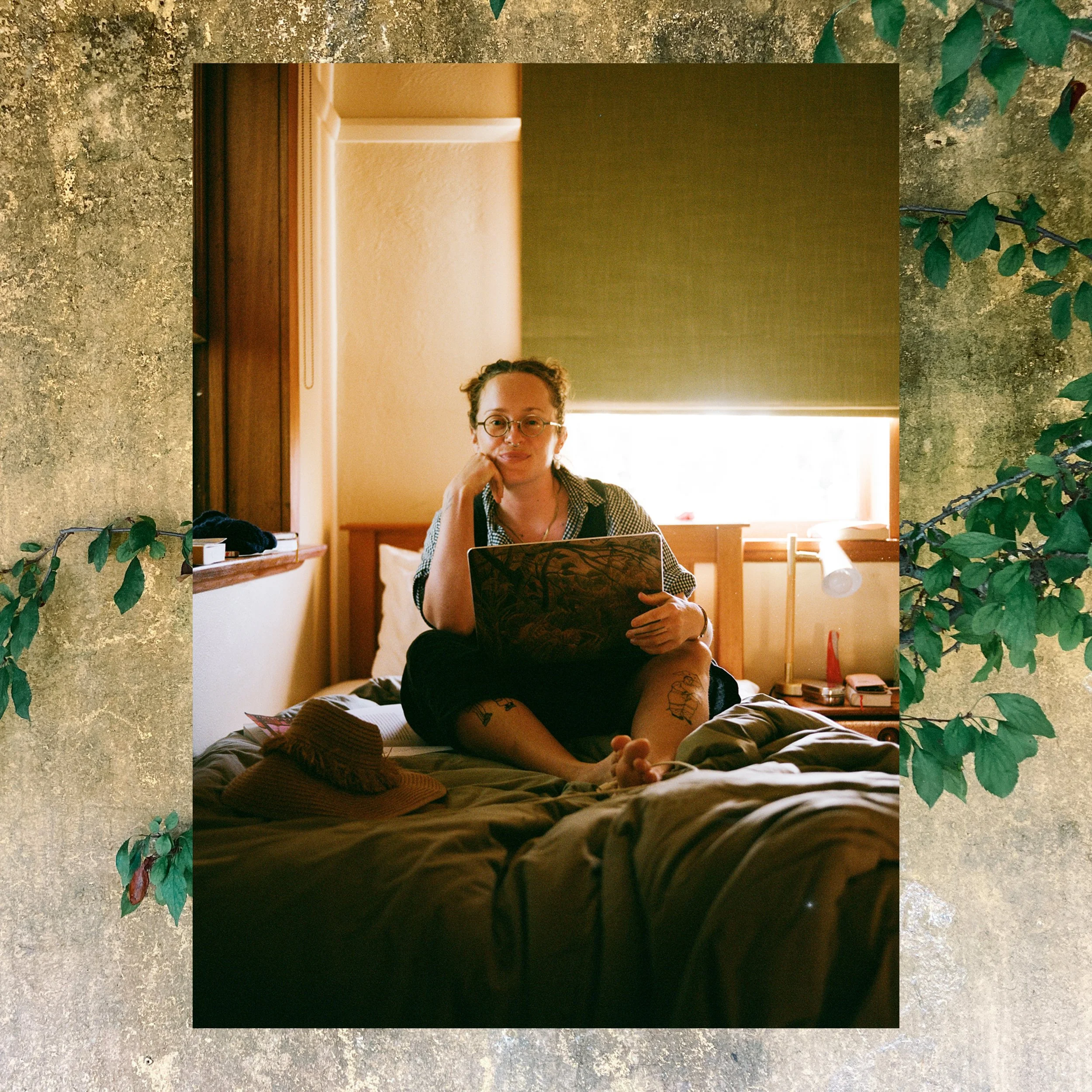

Most-liked photo on social media: this one, of Clementine Ford at Varuna.

New tattoos: five

Bouts of covid: none

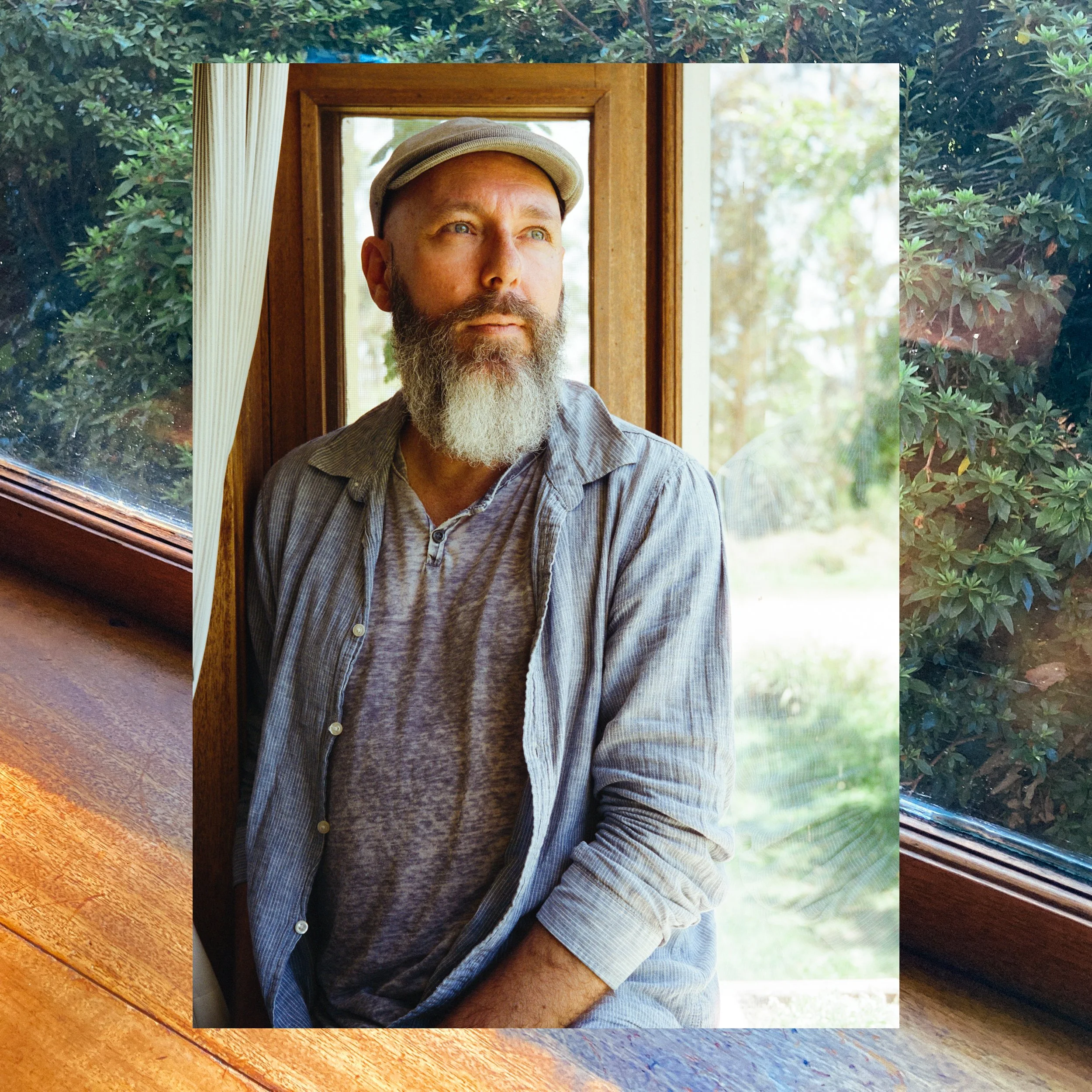

Favourite photo I took: this one of Dom, light painted one morning before crits at RMIT.

Most played song: ‘Slow Mover’ by Angie McMahon.

Song I most often had stuck in my head: this eight seconds of greatness. You’re welcome.

Number of books read: 52

Of which, the best: ‘The Overstory’ by Richard Powers.

Best film I saw: ‘Poor Things.’

Best TV show I watched: ‘Light and Magic.’

Best podcast I listened to: ‘Search Engine’

Submissions (including writing and art prizes, open calls, grants, calls for papers, residencies and labs): 60

Of which, outright successful: 7

Shortlisted but not successful: 4

Furthest distance run: 21.1 km

Total distance run: 422 km

Times I fell over while running: three

Hair colours: four

Hair cuts:: four

Weight fluctuation: 6 kg

Number of names I came up with and subsequently rejected for my new novel: 124

Favourite things I made: two new video works — Jump Scare, riffing on horror soundtracks and the trope of the Final Girl, and Talk Therapy, about inexpressibility and hierarchies of language. And the abovementioned new literary spec fi novel, currently awaiting its final title.

Best decision: asking Sarah Wahjudi to be my exercise accountability buddy.

Best dates: riding to Spensley’s for pizza and wine, making friends with the staff and receiving little gifts of booze and desserts; a drizzly morning at Heide, drinking batch brew and eating croissants, strolling through echoing galleries, holding hands underneath my favourite tree and then sitting in an outdoor enclosure and quietly sketching.

Weddings: three

Funerals: three

Dreams I documented: sixty-eight

People I had sex dreams about: eight

Dreams in which my mother was alive again, and I tried to convince her that she was actually dead: five

Drag names that Mike and I came up with: Agatha Twisties, LinkedIn Park, Victoria Parade, Gary Ola, Franco Costco.

Uncomfortable band names that Mike and I came up with: Edible Undies, Corpse Breeder, Interregnum, Shogunate, Bent Wiener, Hash Hound and the Cash Cow, Obey the Blade, The Edge of Angels, Fair Maidenhead, Nice Guys Finish Last, Righteous Pain, In Memory of Mother

Shittiest day: a friend’s birthday party, Mike having a terrible mental health day and me in a spiral of feeling shockingly lonely and completely unable to communicate.

Last year’s new year’s resolution:

When in doubt, run.

This year’s new year’s resolution:

Get in the slipstream.

Moments that stand out:

On New Year’s Day, we drive to Point Addis. We walk down the steep path onto a beach swamped by a thick, white fog. The ocean is invisible; only sound tells of the crashing of the waves. People stand motionless in the soupy haze. It feels like an omen, somehow. Eventually, the sun comes out and the fog burns away.

At Eastern Beach, I finish a run and realise that my car keys have fallen out of my pocket. I search frantically in the area I was stretching beforehand. Several families try to help. When I head to my car, defeated, I look inside and realise that someone found the keys, unlocked the car, and left them on my driver’s seat. I am both relieved and unsettled by the knowledge that someone has been in here. It feels, somehow, like a robbery.

We go to the RACV Spa in Torquay with Luke and Dani. All four of us lie on the big, marble slab in the middle of the steam room, like sacrifices waiting for the knife. We realise that we can make fart noises by suctioning our back skin on and off the marble. Luke and I sit up to find our backs speckled with blood blisters, our laughing echoing in the misty air.

I lie in the dentist’s chair, mouth cracked open, listening to the scraping of metal on my teeth. ‘Moon River’ comes on the radio, and the dentist, under his mask, starts singing along, his voice rich and buttery.

We visit Matt and Mich. Matt tells us about walking into the hospital and introducing himself as Quinn’s dad — the first time he’d uttered those words. The strangeness and wonder of being a father.

Rachel describes seeing a solar eclipse in the UK; a curtain of black coming off the water, and all the street lights automatically turning on.

We move back to Melbourne. The first day in Northcote, walking through streets lined with eucalypts, I cry with happiness. In the first week, the café down the street gives me free bread. I find a watch in the gutter. Gifts from the city.

Lucy’s dog, Roy, is put down. Five of us hold him, kiss him, tell him he’s a good boy. When the ketamine hits his system, he opens his eyes wide. When the Valium goes through the IV, he lets out a big, beautiful sigh, and slips away. The vet wipes away a tear.

I catch the overnight train to Sydney, on my way to Varuna to work on my novel. An older woman bustles into the sleeper cabin, looks up at my bag in the storage compartment, and snaps, ‘If that falls on me, I’ll sue you.’ I prepare for a long night. As we talk, though, she turns out to be funny and acerbic, flinty and no-nonsense. I tell her that I’m a writer. She says that she’s only recently begun to read books, and now she does so voraciously. Nothing fancy — she especially likes stories of lords and ladies. There is something about her that seems eerily familiar. I realise, as the hours progress, that I am in a train carriage with the lead character from my novel. The night feels almost like a haunting. A full moon shines through a chink in the blind. In the early morning, Lynn and I get breakfast together. I take her photo, we hug, and then she is gone.

At Varuna, the world becomes small and crystal-clear. I write and I rewrite. I run through a bog and down stairs cut into stone. I unlace my shoes and wade into a pool of achingly cold water. I sit under a waterfall, soaking in transcendent joy. At dinner, the other writers tell stories of the ghost of Eleanor Dark. Every night, I bid the ghost goodnight and ask her to leave me be. One evening, Luke talks about Lydia Thorpe’s refusal to compromise on sovereignty, how empowered that makes him feel. How he didn’t realise before just how apologetic he had always felt, just for existing. On the last day, Clementine and I go to a sauna and sit together in a bath of freezing water, knuckles on the rim, breathing in and out through the pain.

On the train home from Geelong after running an event, a woman double-takes when walking past me. ‘Wait, I know you. You’re Julie’s daughter!’ She asks for the details of how mum died. I tell her. ‘We all presumed,’ she says, ‘that she’d killed herself.’

In development with David, I watch him run a game called Busy Mayors with a room full of strangers. I watch his ease in this role, his leadership, his authority and his humour. I feel so lucky to be friends with this man, to work with him. The next day, he cocks his head and asks Jordan, with great earnestness: ‘But what is the plot of Hairy McClairy?’ ‘The plot,’ Jordan says, ‘is dogs.’

Christina and I see Andrew Bird at the Forum, arms around each other as layers of violin and whistles and voice arc over the audience. After, I bum a cigarette from a couple walking ahead of me. I sit in empty Fed Square, looking up at the moon, blowing smoke up towards the clouds.

A friend’s brother dies. I go over to help pick through his apartment, to see what is salvageable. I prod a couch cushion with my foot and look at the blood on the floor that is revealed underneath it. The shape, the spread of it, is remarkable similar to the one left after mum died. Later, I open up the apartment for a woman from the trauma cleaning agency my friend has hired. The woman works for STC Cleaners, profiled in Sarah Krasnostein’s incredible book The Trauma Cleaner, and the documentary Clean. I am enormously excited to meet her. I tell her that I am something of a fangirl for the company. The woman laughs. We stand in the apartment and breathe. ‘It’s very calm,’ she says. ‘There’s no presence left here.’ I nod. I’ve noticed the same thing. ‘Is there ever one?’, I ask. ‘Oh yes,’ she says, and she tells me stories of the lingering dead who make her job difficult.

At the Catherine Opie show at Heide, I stand in front of a wall of landscapes, all of which are out of focus, except for one in the middle. Something about the simplicity of the idea, the reduction of the image frame to a kind of distracted abstraction strikes me deeply.

Roddy calls from outside his dad’s hospital room. ‘I’ve been here for days,’ he says, ‘and I’m just stepping out to go for a walk while talking to you.’ I know already what will happen. We speak about the strangeness of the threshold states of existence. He says goodbye. A few minutes later, he calls me back. ‘My dad died while I was out of the room,’ he says. ‘I know,’ I say. ‘I know.’

Mike and I sit on the sofa and try to figure out the most unhinged ways to kiss. I laugh so hard I wee a little bit.

Sarah rings at 4:45 am. She is in hospital, alone and terrified. Nobody seems to be able to find out what is wrong with her, as more and more of her organs sicken. We talk until the dark lifts, until morning comes.

We hold a house party for Mike’s birthday. I move through the apartment, watching folks meet for the first time, the people lying on sofas, floors and beds. The world feels so warm.

Luke and Dani get married. The morning is chaos, but with the help of a last-minute generator hire, we get everything done just in time. Luke’s face as Dani walks down the aisle makes everything worth it. In her vows, Dani promises to give Luke the love he deserves, the love he hasn’t always had. There’s a ripple through the crowd, from the people who know the weight of those words. Around 1 am, when everyone has gone home, I sit on the sofa and sob with happiness.

In Lismore, Anna, Andrea, Lewis and I stand in the gallery, marvelling at how well our works sit together; how they speak to each other. How the whole is more than the sum of its parts. When Betty talks about the floods, I notice, she doesn’t use that word. She just lifts her hand above her head, to indicate the water level.

Jordan and I go out to dinner to celebrate ten years of friendship. I have just finished reading the draft wild, rhapsodic ending to his book, Big Time. I tell him that I think this book is going to be huge. He waves me away. We cheers to ten years of writing and talking and telling stories, conversations that have no horizon.

At Josh’s house party, the sound system briefly conks out. Someone on the packed, sweaty dancefloor starts singing ‘Hit Me Baby, One More Time,’ and soon everyone has joined in, hot faces shining, beers lifted to the sky.

Luke messages to say that he’s in hospital, after having an anaphylactic reaction to something. He sends photos of his face, which is electric red, his eyes bugging. Mike and I are horrified. ‘Also,’ writes Luke, ‘let’s have a meatball cooking competition sometime soon!’

In Drysdale, I stand on the tip face, photographing dancers dressed as ravens. Whenever a truck empties a load, thousands of seagulls soar into the air, along with a clutch of stately pelicans. This is, I think, a great job that I have.

Amelie, Phil and Derosa’s nearly-four-year-old daughter, has died in the night. Mike and I sit on the sofa and reel with the scale of it, imagining what those parents must be feeling. The churning ocean of shock and rage and grief.

Mike gets back from his first appointment with a psychiatrist. ‘I’m sad he didn’t just press the magic button that makes you better,’ he says.

Steve sits at the pub and quietly cries, lit by the candles on his cake, as we all sing to him for his birthday.

I get up before the sun, lace on my shoes and start running. About 300 metres from home, I trip over on the pavement and graze my knee, elbow and hand badly. Fuck it, I think. I keep running. At about 12 km, I know I’m going to make it. I stagger back home in blazing sunlight and announce to Mike that I’ve just run a half marathon. I call my dad. He’s so proud, he looks as though his face might crack in two.

Mike and I sit in the Malthouse foyer and talk to Ash and Marcus about This is Living. The rawness of the cancer experience; how it strips people to the very bone.

At the end of a five hour assessment, I interrupt the specialist as she natters about logistics and paperwork. ‘Sorry,’ I say, ‘I just want to make sure I’m totally clear on what’s going on. Am I autistic?’ She laughs. ‘Oh, yes,’ she says. ‘And you’ve got ADHD.’ Afterwards, I sit in our living room and try to hold this new information. It hovers like a ball of fizzing light about a foot above my lap. ‘Huh,’ I say. ‘Huh.’

I bathe Maddie and wrap her in her hooded towel to dry her. She pulls the hood over her head. ‘Ooh!,’ I cry, ‘a ghost!’ Her eyes go wide, and she panics, bursts into tears and runs into her bedroom. After some elegant, tender parenting from Jess and Luc, she says to me, with great gravity, ‘I wasn’t sure whether there was a ghost, or whether I was the ghost.’

At yoga, the instructor says: ‘The body reveals. It doesn’t fight.’

I drive Eve to the bus stop. We miss it by about ten seconds. ‘Get back in,’ I say, and we begin a multi-part chase, zipping down Punt Road, trying to get ahead of the bus. When we manage it, she waves victoriously out the window. I feel like a stunt driver.

Dom, Luna and I start a writing group called Write On. Each session, we write for an hour, have lunch, write for another hour and then talk together. I love the way in which even the atoms in a room seem to become more orderly when everyone is in a state of quiet focus.

The Harlots play a packed reunion gig at Shotkickers. The energy in the room is terrific. I look up at Tom, his arms spread, silhouetted in red and blue light. Afterwards, we beg them to get back together. There’s something special on that stage.

Giuls and I are having one of our regular coffee catchups at All Are Welcome. We are talking about prioritising joy in art, about following the way the water is flowing, about looking for signs in the world like orienteering markers. A woman stops on her way out. ‘I overheard you,’ she says, ‘and I really needed to hear that today.’

In Hobart, Christian, Jolyon, Mark and I sit in a hotel room eating Indian takeaway and watch the Matildas beat France, screaming with joy. I love these men, their ease and wit and laughter; how seriously they take the work they do with children.

I go to the doctor. I tell her that I feel out of control of my weight in a way that feels new. She nods. ‘It’s probably the Lexapro. I’ll put you on Ozempic. Everyone’s on it.’ I inject a clear liquid under the skin of my thigh with a needle so small I can’t feel it go in.

Jason and I stand in the RMIT hallway, riffing on a work I’m making based on gallery didactics. Our ideas get more and more ridiculous until we’re cackling, doubled over, saying ‘Yes! Yes!’ Later, we sit in his studio and speak about sex and love and death. The timeless time of dear friendship.

I start volunteering at the Ronald McDonald House in North Fitzroy. I get along marvellously with one of the staff, Jane. She comes to me with a serious expression. ‘I wouldn’t trust anyone other than a PhD student to hang up these laminated cards,’ she says. One day, while filing paperwork, I come across a note on a file: ‘Baby X died on April 7.’ I think about how someone spent my birthday weeping over a NICU cot.

Mike and I watch Grayson Perry’s documentary about men and suicide. I sit on the floor between his knees and we talk, hard and dark. We are both crying, holding each other in the fear and sadness and dread.

In a PhD meeting, Sally carefully tells me that the work I’ve been making is too quick, too surface level. I talk about being afraid that I don’t know how to make good, refined work, and try not to cry, and fail. Dom and Sally are both so kind and generous about strategies for working through the not knowing. Dom calls me on his way home. I answer, and his first words are, ‘I don’t know how to make art either! But we just figure it out together!’ I am grateful, I am grateful.

Luke has developed a musical alter ego: a country star called Dallas Dallas. He sings us his debut country song, and after a few choruses, the whole family is singing along around the table, giggling at the lyrics.

At the Fringe, we watch Pony Cam’s Burnout Paradise. I’ve never seen a show get the audience so quickly onside and passionately involved in participation in my life. It is a masterclass in a simple idea well executed. Chaotic joy.

I am with friends when the referendum results come in. We all go quiet, scrolling through our phones. ‘Imagine,’ someone says, ‘being proud to be an Australian.’

Luke runs his first marathon. We catch him at the 32 km mark — ‘This sucks,’ is his succinct assessment. By the 40 km point, he is cramping so badly he can hardly walk. Dani runs alongside him, passes him a shot of pickle juice, and 30 seconds later he is running again, into the MCG. Glory.

I have a cyst excised from my cheek. I am awake during the procedure, and one of the nurses keeps her hand resting lightly on mine. I am always so moved by these small acts of care in medical settings. That night, I go to Lewis’ opening at Kings, and have to hold the side of my lips closed in order to speak, so strong is the local anaesthetic.

Mike and I sit on the bedroom floor. I show him my new video work, and he shows me the Greenday video he animated in a week flat. We both marvel at each other’s output. A sweet show and tell.

Dad calls to say that Luke has fallen off a ladder. He has dislocated his shoulder; his fingers are broken, probably his wrist as well. When I get onto Luke the next day, he’s at the hospital. I ask, ‘Did you not go straight there last night?’ ‘Nah,’ he says. ‘I relocated my shoulder, and then we had dinner. Oh, by the way, we’ve just been approved to buy our house.’ I’m bemused, but I can’t help but laugh.

In Sydney, I swim at the women’s baths, totally alone. I pull off my bathers and nose through the water, gliding above fish and crabs. If there is a better feeling than being naked in the ocean, I do not know it.

I am shooting tweens at a community centre. Two boys are hogging the good trampoline, doing flips and being aggressive to a younger girl who wants a turn. I tell the ringleader, ‘Look mate, you have to let her have a go.’ ‘Why?’, he asks, nose wrinkled. ‘Because,’ I say, ‘sometimes, it’s good to not be a dick.’ He blinks, exchanges glances with his friend, and they step off the trampoline.

Mike and I sit on the sofa and play a video game called Pikuniku. We’re meant to be moving some balls through a course, but we keep accidentally kicking each other in the head. Every time it happens, it gets funnier, until we’re almost crying with laughter.

We go to Dom and Siobhan’s place for lunch. Mike, Dom and Lewin talk with great seriousness about kaiju films. Siobhan, Tally and I compete in a grand obstacle course in the backyard. The sweetness of befriending a whole family. A few weeks later, Dom texts me to say that Tally woke up and said, ‘I know today is going to be a good day because I’m going to see Sarah.’ My heart nearly explodes.

Hi-Viz Lab, the joy of being surrounded by artists, women, non-binary folks. I sit in a windowsill with Weish and we talk about the complexities of growing up in colonial settings: me in Australia; her in Singapore. With Aviva, we walk with closed eyes through Carlton, holding onto an extension lead and trying not to stumble. Josephine writes a manifesto and delivers it to the sky, standing on a pile of stone like a prophetess.

The cactus in our bathroom is blooming. Every time I see its extravagant red flowers, I feel a catch in my heart, a jag of melancholy and wonder.

Shabbat at Luke and Dani’s new house. The care with which Dani lights the candles, the gravity with which Mikey intones the prayers. Two nights later, we gather again for Christmas Eve, playing games on the floor until everyone is yawning and blinking. I am still astonished to be near them, to have them back from London.

I have lunch and play games with Sarah and Han. Sarah talks about how integral play is for her, how she asks for it in her marriage, because it keeps her going. I love this idea. Prioritising silliness, ease, light. Prioritising what is simple and good.

S x