2022

States visited: two

Plane flights: two

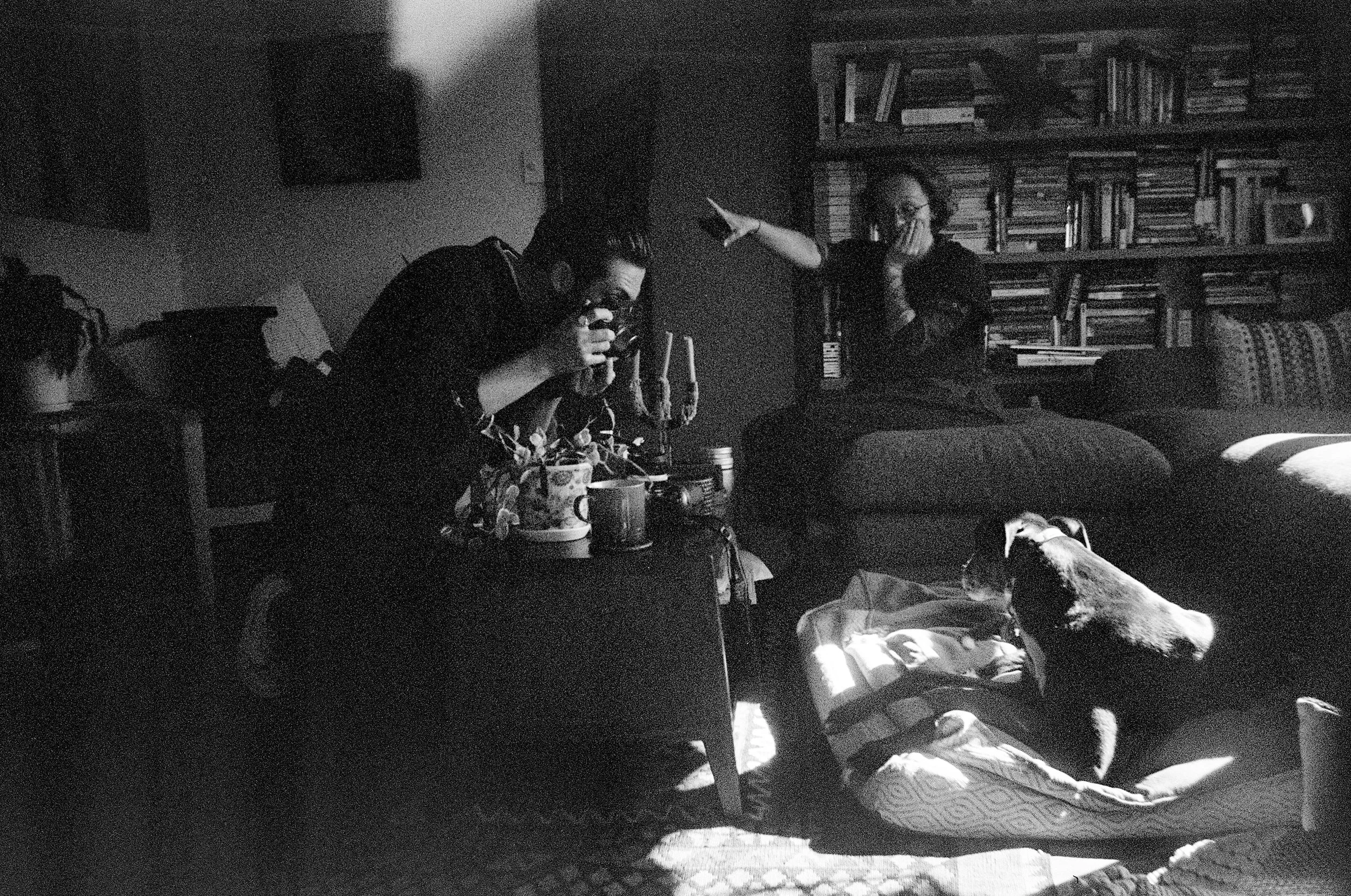

Most-liked photo on social media: this one, taken on my birthday.

New tattoos: two

Migraines: two

Bouts of covid: one

RATs: 58

Seasonal videos made: one (covering our first forays out after the lockdowns of 2021, to the end of summer)

Most played song: ‘Seventeen’ by Sharon Van Etten feat. Norah Jones.

Song I most often had stuck in my head: ‘Chaise Longue’ by Wet Leg.

Number of books read: 51

Of which, the best: ‘Piranesi’ by Susanna Clarke.

Best film I saw: ‘Good Luck to You, Leo Grande.’

Best tv show I watched: ‘Severance.’

Dungeons and Dragons characters played: two

Most words written in one weekend: 10,000

Numbers of people I killed in my writing: eight

Money earned from writing: $4738.20

Money earned from teaching: $8761.15

Favourite things I made: two published pieces: ‘Fontanelle’, a piece of fiction for Overland about the precariat; and ‘Little Breaks’, an essay for the Monthly about surfing and sad men.

Best decision: letting a new doctor finally convince me to go on SSRIs.

Best date: a walk to Buck Mulligan’s, whiskey, bright conversation, a stumble home with our faces warm against the outside chill.

Weddings: two

Funerals: two

Ashes scatterings: two

Notebooks filled: two

Decisions I regret: two

Butt dials from friends: sixteen

Shittiest day: Monday, September 5, sitting clutching a cushion in Mike’s brother’s house, shaking with a panic attack, trying to breathe, knowing I couldn’t get on a plane.

Last year’s new year’s resolutions:

Return strength to this body. Be brave.

This year’s new year’s resolutions:

When in doubt, run.

Moments that stand out:

January

Ben calls. He has a favour to ask of me. Of course, I say, anything. He asks me to act as the celebrant for his and Lucile’s wedding, to tell the story of their love. I am deeply moved by the request. I tell him, too, that I have booked into a deathwalker course in June. ‘Perfect.’ he says, ‘I’ll still be alive in June. You can walk me.’

Mike sits on the front fence as I weed the garden, reading to me about Bigfoot theories. We are both delighted to learn that anthropologist and primatologist Jane Goodall is among those who want to believe.

I am writing a thousand words every day. A character, then a place, then a story blooms into being. A novel; my first.

Ben’s birthday. Face masks and tears. He makes a speech, a proud, brave, powerful speech. About how this will be his last birthday. About how he wants to bring people closer, to speak to them, to be honest and open.

‘I am hoping,’ he says, ‘that in a way, this will be the best year of my life.’

He tells us that he is seeking Voluntary Assisted Dying.

When he steps down, I hug him and whisper, ‘I’m so proud of you,’ and he says, ‘You inspire me so much.’

Later, I hold his face and say, ‘I’m so glad we get to be alive at the same time, for a little while.’

Sarah, Ilana and I install text works around Geelong, haphazardly, using our feet to hold the stickers in place while we peel them back. A day of laughter, bright sun.

I drive towards Melbourne, to meet with Ben and Lucile. Outside Werribee, the anxiety is too much. I pull over, sobbing in the heat. Mike leaves work, drives me to Northcote. I speak with my friends about their love for each other. Ben’s head is back on a pillow, his hand on Lucile’s thigh.

We head to Vaughan for a weekend away. The house is beautiful. Soaring ceilings and reclaimed timber. We drive into Castlemaine for breakfast, and panic slides up my throat. I am doubled over on the floor of our van as waves of terror and nausea crash over me. I take valium; it barely helps. ‘I hate this,’ I say to Mike, gasping. I feel as though I am drowning.

I sit out the back of the house, drawing on the driveway in chalk with Maddie, aged four.

‘This is a caravan,’ she says. ‘The caravan is going to space!’

The magic of her multi-point visual perspective, horizontals and verticals all folding over each other and out on the ground.

We swim with Martin and Helen at Eastern Beach as lightning flickers on the horizon. We make it inside moments before an almighty storm breaks. Sheets of water block out the whole ocean. The light turns yellow, like sodium streetlights.

February

Luc holds water in his cheeks like a chipmunk and manages to still speak. I try, and the harder I try, the more Mike and Jess giggle.

‘Don’t laugh,’ Luc says gravely. ‘Whatever you do, don’t laugh.’

I buckle with mirth, water spurting from my lips like a fountain.

Ben and Lucile’s wedding. A stunning day. A festival of extraordinary love and grace. Aviva weaving through the garden, playing the clarinet. Mick setting megaphones to loop the sound. Ben’s bright eyes. Michel’s big-hearted fatherly love for everyone. Lucile’s lips in red. Mike and Gab laughing so hard they are crying. A vast lantern bobbing over the dancefloor. Looking out over the sweaty faces and raised hands, I think, ‘this is such a joyous celebration of life.’

Luc, hungover, gets up and potters around the kitchen. It takes him several minutes to notice that we’ve scrubbed and tidied. He does a double-take. ‘What the fuck happened to our house?’

Lounging on Chrissie and Rachel’s sofa, Chrissie refers to Mike and I as ‘tracksuit pants friends’ — those with whom you feel totally comfortable. This pleases us very much.

I step outside the development room in Seddon when Lucile calls. ‘It’s a shitshow,’ she says. Ben has weeks to live.

I see Ben. I am all wrong. I can’t tell what tone I need to bring, what words to say.

‘I don’t know why I’m so tired,’ he says.

‘Ben, you’re dying,’ I say, and then I make some stupid joke when he spills tea on himself, and he dismisses me so he can go to bed. I leave thinking, you fucking idiot. You fool.

Mick calls. He urges me to come and stay in Melbourne. Ben has only been awake for 25 minutes in the last 24 hours.

‘I think we’re no longer looking at the end,’ says Mick,' ‘but the beginning.’

We rent an apartment in Westgarth. I see Ben. He is naked under the sheets, and when I come in, he struggles out of bed to pull on underwear and a t-shirt. His body is that of an old, old man. He looks at me, eyes bright in his skull. He says something. I can’t make it out. He says it again, more emphatically.

‘I’m sorry,’ I say. ‘I’m sorry Ben, I don’t understand.’

He slumps back in the bed. He sleeps. I never find out what it was he was trying to say to me.

I ride to meet Mick and Amaara, to talk about what is to come. On the way home, the moon is huge and yellow in the sky, as though it is coming down to swallow us all.

I go to the showing of David’s new theatre work. It’s about the climate crisis, the bushfires, the history of humans learning the wrong thing from disaster. It ends with a terrible, unstoppable list of all the ways we’re fucking the planet. I excuse myself and rush to the toilet to sob quietly. I recognise the shoes in the next cubicle over.

‘Jordan?’, I say. ‘Are you having a cry, too?’

We both come out and hold each other by the sinks and sniff into each other’s shoulders.

I am standing onstage at Her Majesty’s Theatre, filming video for an ABC story. I get a text from Briohny. Ben has died. I look out across wood and velvet, into darkness. The day is a rush of fast and slow time. Tears and light and hugs. An all-in BBQ in the back yard, because we know everyone needs something to do with their hands.

March

After Ben’s funeral, a group of us drive to Williamstown beach and jump in the ocean. The feeling of being cleansed from the soul outward.

‘It’s 11:11!’ I say to Mike.

’Ooh!’ he says. ‘A spooky time! So many legs!’

This tickles me greatly.

Mike and I do a ring-making workshop, carving wax to fit each other’s fingers. On the way home, Lucile texts that Ben had wished that Mike and I hadn’t moved to Geelong; that he would have loved to live with us. On the radio, Paul Simon sings, ‘these are the days of miracle and wonder / don’t cry, baby, don’t cry.’

I cry.

In my first day as a lecturer, I ask students to give their pronouns if they’re comfortable doing so. One student comes up in the break and whispers, ‘I said in front of everyone that my pronouns are she/her, but I wanted to tell you that they’re actually they/them.’ We share a grave nod of shared knowledge. I am immediately fond of them. Anyone who says teachers don’t have favourites is a liar.

Katerina talks about articulating the three most important things in your life. Hers are work, family, travel. Mine, I decide, are discovery, novelty and intimacy. She tilts her head. ‘You probably shouldn’t have children, then.’

Aviva dives into the water at Eastern Beach with a knife and emerges with fistfuls of mussels. She cooks them in a broth and we taste them, eyes wide with wonder.

I life model for a local secondary school. I stroll around, looking at their renderings of my body. One of the girls has drawn me surrounded by sigils.

‘Cool,’ I say, ‘I look like a witch!’

She nods at me seriously. ‘You have a really cool aura.’

The sense that death is so proximate, approaching at every second. Which it is, I suppose. I just feel it more than usual.

I stay at Dad and Yvonne’s. I crawl in between them in the morning to do the Wordle together. The childish pleasure and safety of that.

April

A man at Southern Cross station lays down his jacket in front of a bench, kneels and prays. Simple beauty.

Katerina and I have a development at a gallery in Collingwood, in a tiny room on Hoddle Street. We are working on a sound work. This is made difficult, firstly by the traffic, then by the roar of an extractor fan behind the wall, then by the slaps, groans and wails from the kink workshop going on next door. I get a migraine. I lie on the floor, quiet in the midst of a tornado of noise. The next day, we cannot access the gallery for hours, because there is a man dead on the road outside. The way that the existential clashes with the practical. It is horrible, yes, but we are also waiting for the police to let us in so we can work.

Mike and I are in Lakes Entrance for Easter with his family. We run along a bush track, then walk down the beach, talking, wondering whether salt water is heavier or lighter than lake water. I love this man, his curiosity, his gentleness, his questioning spirit.

I am exhausted. I wake in the night to the sound of the dog tap dancing around the bed. I am filled with rage so intense that I think my head might actually explode.

May

On the train, a man tries to sit next to a woman in her thirties. ‘No,’ she says. He gets belligerent. She moves seats, shaking, crying. I step over.

‘Did you want me to sit with you?’, I ask. She nods. I can feel her distress boiling out of her. It feels good, to offer some small comfort just with my presence.

Later in the week, a group of young islander men get on the train. They are loud, boisterous. One of them turns on a boombox, and out blares Michael Jackson’s ‘You Are Not Alone.’ All of them sing along, crooning, hands on hearts. I am grinning so hard under my mask that my glasses are fogging up.

I am seeing a new psychologist. I have my first EMDR session. I notice, with interest, the way the camera angles change on a memory, from a POV shot to a wide, from the back.

We drive to Portland and hike through bush to a remote beach to scatter Ben’s ashes. As we walk, the person in front of me turns around and passes the ashes to me, so I can carry them, so I can hold Ben on this last journey. Snot is running down my face. I walk with him. I turn and pass him back along the line. On the beach, Lucile, Eva, Les and Leah wade into churning water, pummelled by sideways rain and terrible wind. Once the ashes are in the sea, so suddenly it is eerie, the wind stills, the rain eases. The sun comes out. A rainbow appears.

I record dad for a video work. He hams up his part, improvising lines, coming up with jokes. We burst out laughing at each other. The generosity of it.

I am due to fly to Sydney in the morning for Sydney Writer’s Festival. My throat is sore. From six hours of lecturing, I presume. I take a RAT, just in case. It is positive. The next day, my lecture at the festival is cancelled. They don’t have the infrastructure to do it over Zoom. In the backyard, I lift a milk crate and slam it down, over and over.

There has been an odd pain in my back for several days. Now it erupts into shingles.

My SWF panel with Chloe Hooper is on Zoom. I am wearing lipstick and a shirt on top, and flour-covered pants and ugg boots below. The wifi on the Sydney end keeps dropping out. Anton Enus introduces me using the wrong bio — he has evidently Googled ‘Sarah Walker’ and found the writer who worked on All Saints, for whom I occasionally get fan mail. The conversation is awkward, stumbling. After, I am tired and lonely. Jordan and Anna FaceTime me from Sydney and we talk nonsense until 2 am. It is a tonic. I am grateful.

I allow myself one shot of gin on election night. Mike is sleeping in the back room, to avoid getting covid. I wake in the night. My resting heart rate is usually around 55. Now, it is 152. I wait. It doesn’t go down. I try to make a call. My phone is out of credit. I stagger out the back. Mike calls an ambulance. Masks and tedium and fear. Eventually, over a video call, an ER doctor tells me it’s probably from the shingles antivirals mixed with the covid. The paramedics are kind. They tell us about the program that means they sometimes get to cuddle a dog on shift, for their mental health. Their eyes light up when they tell us. It’s the best part of the job, they say.

We do a development showing of Bodies of Water, the audio work that Katerina and I are making at Eastern Beach. The theatre of the sun going down over the ocean never fails to be staggering. Rachel, over tea, describes it: ‘We were being chased by the dark.’

My body is a mess post-covid. Terrible fatigue. I shoot several plays kneeling on the floor, because standing floods me with dizziness and anxiety.

June

In the recording booth for The Future of Everything, Mike’s show, Andrea Powell lets out a series of Hollywood-perfect horror movie screams. Granger, the sound recordist, is awed.

Mike and I move into a room at Ben and Lucile’s house, part-time. The house has a particular smell. I thought, at the time, it was associated with Ben’s illness. A cleaning product, perhaps. I could never place the scent. It is still here. The house is thick with it.

Luc calls to tell us that Jess has just given birth to Felix. We jump on the tram and toast with whiskey. Luc is wild-eyed and overjoyed, astonished by Jess giving birth in three pushes.

A line in Ben’s PhD, describing a day we spent testing what it feels like to have blindfolded conversations: ‘I feel closer to Sarah than I have to anyone in a long time.’ Weeping.

I see Invisible Opera for Rising. It is freezing cold. I am laughing out loud, trying to figure out what is real and what is planted. The joy of uncertainty, of liveness, of silliness.

I get an email. I’ve been offered a PhD scholarship. I begin in two weeks. I am nervous and thrilled.

I nearly cancel the deathwalker workshop. I am so tired, so jangly, so scared that it will be three days of people competing with their traumas and talking about ‘holding space’ and ‘honouring your truth.’ Instead, it is profoundly invigorating, thrilling. There is laughter. There is frankness. There is leadership and presence and grace. I leave full of light.

Two friends refer to me as queer on the same day. I am surprised by how moving I find this; how validated I feel, to know that I am known in that way.

In a D&D game, we discuss a rift in the cosmos that requires the blood of innocents to keep it closed.

‘What happens if you put a horse in the rift?’, I ask.

Ben narrows his eyes. ‘Horses are never innocent.’

July

The woman in the car in front of me is on a Bluetooth call. I can see the big letters on the screen denoting the caller. ‘GIOVANNI’, it says, and then, perplexingly, ‘MY HUSBAND.’ I wonder who she’s trying to remind.

Jordan and I get the train to Warrnambool for a writing retreat. We walk to the beach, under an extraordinary sunset. We win $40 at the pokies. We go to a bathhouse. We sleep in little twin beds in a motel, like an old married couple. I write ten thousand words in a kind of craze of effort.

We move back out of Northcote; Lucile is not ready for housemates with schedules as unpredictable as ours. Mike and I start to talk seriously about moving back to Melbourne, about leaving Geelong.

My anxiety is so strong I feel pushed out of my own body; occupied by an invading force. I go to the gym and work so hard I can hardly walk.

Mike and I spontaneously book a holiday in Bali for September. A whole month, in the sun.

I wake up from a gastroscopy and colonoscopy shivering. The nurse covers me in a warm blanket. This is one of the best sensations I have ever experienced.

I sit on the floor in a Fitzroy AirBnB with Fleur. Her head is on my shoulder as we sing together, harmonising.

I go bouldering with Mo, and watch them stepping gracefully from hold to hold, pressing an arm against a slab of wall. It is a tender power.

My Self in That Moment opens. Jess, barely lit, roils, her mouth open, the many distended mouths on her costume also open, a scream of birth and fear. Remarkable.

Jordan and I have a boys’ night. We watch Die Hard and drink wine and talk until 4 am. The way conversation in old friendships is never-ending, infinite, ongoing and full of delight.

August

I have tea with Tom Holloway and talk about death and art. He mentions a project he’s trying to pull together, about doing a Death Care Plan onstage with a volunteer. After I’ve left, I send a shy message offering to be involved if I could be of use. ‘I was hoping you might say something like that’, he writes.

I go to a Sea Shanties and Folk Song event at the Mission to Seafarers. I end up leading two songs I know well, and am so happy my body doesn’t quite know what to do about it.

Maddie and I lie on the trampoline at Hoddles Creek. The moon is visible in the blue sky. We yell at the moon to go to bed and come back later.

‘Go get lunch, moon!’, she yells.

We rock onto our backs and kick our legs in the air, bellowing.

At MIFF, Mike, Jordan, Jessa and I watch Triangle of Sadness. During the 20 minute storm-vomit-shit sequence, I stuff my fingers in my ears and shut my eyes tight, like a child.

I finish a shoot, walk into the city and am swamped with a terrible feeling I have no words for. Dread, horror, deadness. It feels as though a black, electric tsunami has collapsed onto me. It passes a little, but I lie awake at 4 am, terrified of feeling it again.

I am sitting at a bus stop near Footscray station, idly thumbing through my phone. A man approaches me.

‘Can you call an ambulance? That woman has been hit by a bus.’

He points. It looks like the start of The Wizard of Oz; feet under a wall. Someone is already calling an ambulance. The bus reverses off the woman. The injury isn’t as bad as it looked; she hasn’t gone under the wheels. Her head hurts. People are yelling and screaming about not touching her. Nobody is talking to her. I kneel down, take her hand. Ask her name. When the ambulance comes, I find the bus driver. He is sitting on the step of the bus, staring at nothing. I buy him a lemonade. I speak to him. When the cops come and make me leave, he hugs me.

‘Thank you,’ he says. ‘You are an angel, sent to look after me.’

When Tam picks me up and I tell her the story, she says, ‘Things like this seem to happen to you a lot.’

I get my doctor’s appointment time wrong by fifteen minutes. She is annoyed. I burst into tears.

‘I’m not okay,’ I say. ‘I feel so sick all the time. Every part of me feels deeply wrong.’

She huffs. ‘Sounds more like mental health deterioration to me,’ and sends me out.

I see another doctor. I tell her I’m meant to be going overseas in a few days. She looks at my prescriptions.

‘Why aren’t you on an SSRI?’, she asks.

‘I’ve always been scared of the side effects,’ I say.

‘You can’t feel much worse than you do now,’ she says. I take my first dose of Lexapro.

September

The hours tick forward. I cannot travel. I cannot move. The Lexapro has increased my anxiety such that I am a walking wound, a trembling marsupial. Jetstar moves our Bali flights, and offers us a refund for them. We take it. I spend two weeks at home, in bed, frightened, shocked, exhausted. Mike tries not to show how sad he is. The strain of it.

I begin to come out of the freeze. I have the energy to exercise. Slowly, slowly. I call Lucy. We talk about somatic coping mechanisms, rather than just thought-based ones.

‘Has anyone ever suggested to you that you might be autistic?’, she asks. I scoff.

I ask another autistic friend. ‘Oh yeah,’ they say. ‘I’ve always thought that.’

I talk to my psychologist. I talk to a psychiatrist.

‘I mean, sure,’ they say. ‘Checks out.’

For the first time in my life, I let myself consider my anxiety to be partly a reaction to overstimulation. I look back at my childhood self, who I’ve always spoken about with scorn, and think, ‘huh.’

Sarah Jones suggests a giant wall of hay bales as a shooting gallery for my solo show in Geelong.

‘Yes!’, I yell. ‘Yes!’

We fly to Cairns, spend a week there, and then head to Palm Cove. Most mornings, I go for a run. We walk ten kilometres each day. We snorkel and kayak and swim. I lie by pools and read books in giant gulps and get terribly sunburned. After years of exhaustion, I am shocked by the energy I have for movement. The relief of it.

At a swimming hole near Cairns, we watch a young man, maybe fifteen, scramble up a high rock face, tiptoe out to the edge, and then throw himself into the water far below. When he comes back up, his family are laughing and chiding him. He sits on a rock next to me. I hear him say to himself, quietly, ‘I will never, ever forget that.’

October

In the bath, I lie on Mike’s chest. He strokes my back in the water. I feel like a child. Safe. Sweet.

Uncle Jack’s funeral. The effortless blend of solemnity and levity. The simple ceremony of placing leaves on the fire, touching the coffin with reverence and love.

I go to the Schwartz Media offices on a rainy day to record my piece from The Monthly to go on the 7 am podcast. I drop into the editor’s office and he is full of praise. I walk down the stairs, feeling smug, and then, on the bottom step, I slip extravagantly and fall on my arse. A businessman down the street watches me with alarm as I stand up, limping and cackling.

We run two events to distribute Ben’s PhD writing. People gather and share their connection to him; watch his remarkable last milestone presentation. That week, I am at Southern Cross station when a huge storm breaks. Rain pelting the roof, lightning. Hundreds of people gather in the station and stare out at the water hitting the street. I run up the stairs, feeling electric, overjoyed, thrilled to be alive.

Jason helps me install my solo show at the gallery. Mike’s show premieres at Austin Film Festival on the same day as my opening. When I finish my performance, and put down the bow I’ve been firing, I look over at dad, who is clapping hard, misty-eyed and proud.

November

I am by the river, as an artist talks about circular time, about linearity being a myth. I keep having to step out of the session to help book Mike a flight home because his Nan has had a stroke.

‘This time I’m in right now feels very linear,’ I say. ‘The line between birth and death. It doesn’t feel circular at all.’

Our house goes on the market. I rewrite the marketing copy and re-edit the photos. We pack half our stuff into the shed and pretend to be minimalists, stripping the home bare so people can imagine themselves into the house.

I go skating with Mo and Kai, toppling happily in a pair of roller blades. The new medication makes itself known in funny small ways. I hurtle down a slope on Kai’s skateboard, and my fear is soft, gentle. It feels like someone has taken my anxiety and turned the gain down. It’s not peaking nearly as easily.

I sit in Dom’s office and do my Confirmation of Candidature online. I pass. I can now officially call myself a PhD student.

I will never be a good runner. My body isn’t built for it. But the calm that comes after a hard run is like nothing else.

We host a screening of Mike’s show for friends. The house is full of love and booze and great conversation. All those people, loving the man I am most proud of. It feels brilliant.

Jacko has broken his toe at the dog park. The emergency vet talks amputation, $6000 surgeries. Our normal vet suggests we just see what happens. He hobbles around, yelping when he accidentally knocks it. Slowly, slowly, he stops limping. Slowly, slowly, it heals.

We sit on the floor in the hallways as our house goes to auction. It all happens so fast. Once we hit our reserve, I start jiggling up and down. Mike puts out a hand to quiet me. When the auctioneer and the winning bidders come in, they’re all sweating, full of adrenalin. Mike and I sit outside and wait for them to do the paperwork. A woman from the real estate agent cocks her head at us.

‘Usually people are screaming or crying and drinking champagne right now,’ she says.

‘Oh,’ I say. ‘We’re just relieved, I think.’

December

The Bodies of Water season. Voices and sunsets and people stepping, shrieking into the cold water. A beautiful thing.

Mike and I sit in a wine bar in Fairfield, tallying up travel distances for two apartments. How far to the Westgarth? How long to RMIT? We inspect the Northcote apartment again. Walk around the back streets, nodding, saying, ‘Yes, we could live here.’

I run 5 kilometres for the first time in a long time. That night, the moon huddles behind a cloud, making the sky look strange and inky. As Mike and I watch, the moon emerges, full, bright, a show for us alone.

At Flagstaff Gardens, a possum trundles over and sniffs my sandaled foot. A man zooms past on a bike, yelling, ‘Don’t touch it!’

We sit in a real estate agent’s office with another couple who are carbon copies of us, and bid for an apartment. They step down $3000 from our maximum price. They’ll never know how close they were to winning it. We shake hands.

‘Sorry,’ we say. ‘We hope you find somewhere wonderful.’

We go to the Wesley Anne and drink wine until the shock wears off.

Danny and Lucy’s wedding. Incredibly moving to be surrounded by people I’ve known for over a decade. I watch Danny on the dancefloor, holding his friends with fierce love, men pressed against each other, smiling and sweating onto each other’s shoulders.

At my uncle and aunts’ house in Adelaide, I see my brother and Dani for the first time in over two years. Christmas is full of tears of joy and love.

We scatter mum’s ashes at the river property she loved, improvising a ceremony, marking spaces of importance. The river is in flood as never before. From horizon to horizon, there is nothing but water and trees and sky.

S x