2021

Countries visited: none

States visited: two

Plane flights: six

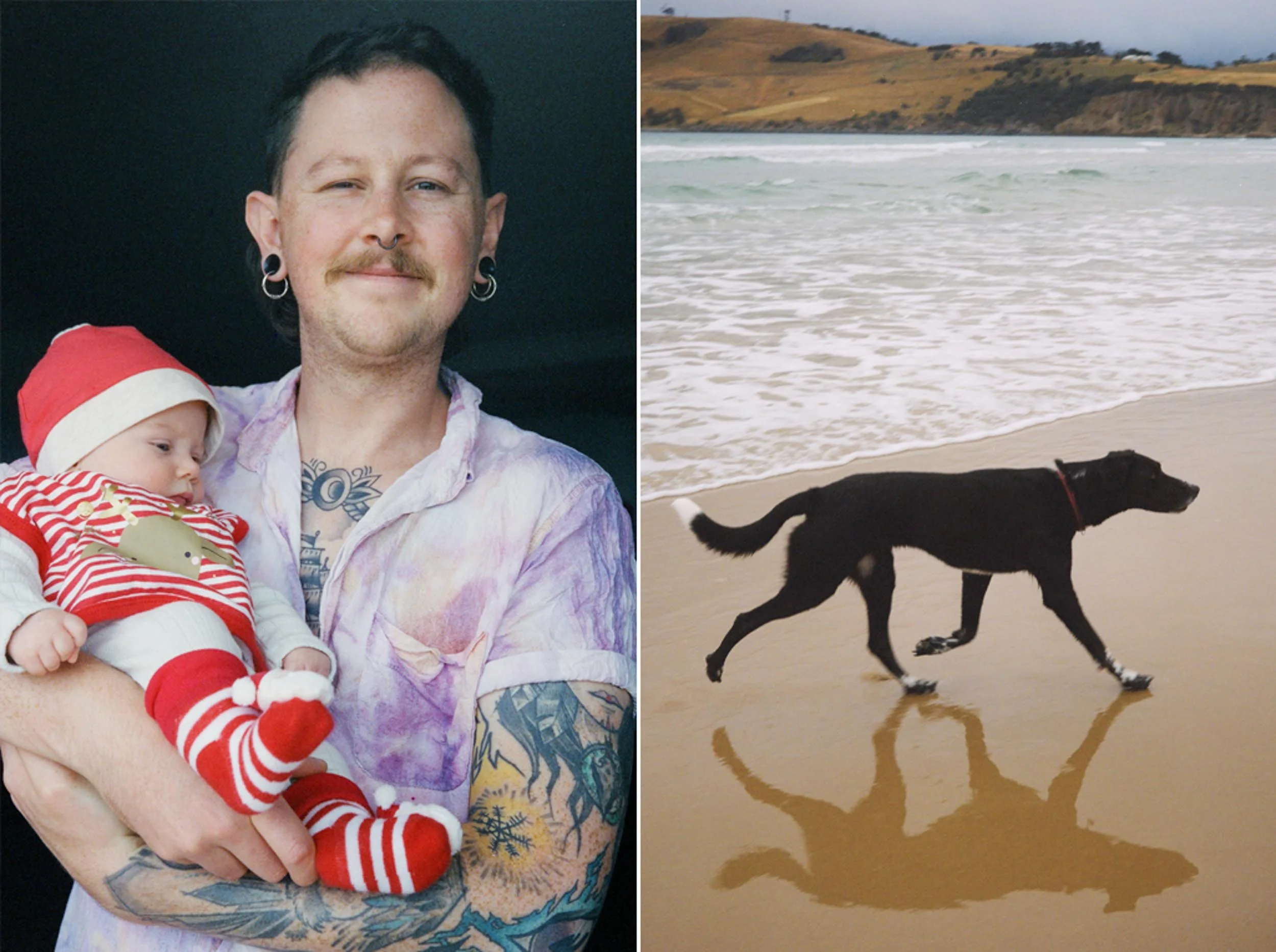

Most-liked photo on social media: this photo taken by Mike, of the day I received my author’s copies of The First Time I Was Dying.

Migraines: five

Covid tests: fourteen

Of which, negative: fourteen

New tattoos: three

Most-played album: The Decemberists — ‘The King is Dead’ and Phoebe Bridgers — ‘Punisher.’

Most played song: ‘Halloween’ by Phoebe Bridgers.

Song I most often had stuck in my head: the default hold music for Cisco phone systems (largely as a result of this video).

Number of books read: 48

Of which, the best: ‘How to End a Story’ by Helen Garner and ‘The Golden Gate’ by Vikram Seth.

Number of books written: one

Dungeons and Dragons characters played: three

Favourite things I made: a new book, as yet unpublished, and ‘Colosseum’ for The Unconformity.

Best decision: on lockdown days, demanding of myself only that I exercise and cook a beautiful meal.

Best date: a spontaneous trip to Anglesea, canoeing on the river, shouting with the beauty of it.

Best piece of practical knowledge gained: not every whipper snipper needs the line to be hand-fed every time it breaks. Bump feeders exist.

Notebooks filled: three

Devastated conversations with friends and colleagues whose projects had been cancelled on opening night: five

Shittiest day: some time in September, so anxious my mind started fraying at the seams, when just leaving the house felt too dangerous to bear.

Moments I felt so happy I could burst: working in Queenstown, the glorious coalescing of people and place and gear, the kindness of the locals, Ian Pidd’s face as he said, quietly, ‘I am happier right now than I have been in quite some time.’ Every time I saw my dad, even when I was terrified. The day I finished a new manuscript. The first strawberry of summer. Cooking steak in a cast iron pan. Mornings in a beam of sunlight, drinking coffee. Every time Maddie called me ‘Sisi.’ My brother’s face, on a phone screen, smiling.

Last year’s new year’s resolutions:

Find the still in the storm.

This year’s new year’s resolutions:

Return strength to this body. Be brave.

Moments that stand out:

January

I write. I begin with no planning and no plotting, no themes and no form. From nothing, words begin to emerge, to coalesce. Short fiction. Strange rumbling disasters ending at the moment of crisis. I do not know quite what it is, yet.

Mike and I go to UrbnSurf. I watch him coasting down perfectly engineered waves. When he comes in, he is breathless and grinning. I paddle out for the longboard session. When the wave rears up under me, I panic. One of the staff, sitting on his board, asks, ‘Are you scared about nosediving?’ I nod. ‘If you turn down the face of the wave, you won’t’, he says. I try four or five times. I fight a battle between fear and pride. Fear wins. I paddle into shore, shaking. Even this false, chlorinated ocean is too much for me.

I do an online Qigong class, standing in front of my computer, while a man who cannot see me says, ‘Good, good.’ I push the air with my hands.

February

I photograph a Mirka Mora exhibition for the Jewish Museum. There is a little section of home video footage of her, big skirted, laughing; topless, lifting children towards the sun; drinking, perfectly sidelit by a window. She is so deeply, miraculously alive. There is a mischief to her, a glee, that delights me.

I am running ahead of Bridget as she listens to my sound walk along the Upfield Bike Path. The sun seems to catch in my eyes. It takes me a minute or so to recognise the start of a migraine aura. I photograph through vision whose middle is dancing, fizzing static.

A feeling begins. It is similar to the early hours of a urinary tract infection. Pressure, discomfort. I need to piss constantly. Urine tests come back clear. Day after day, the pain worsens. One afternoon, Mike and I drive to the beach, intending to surf. Instead, I lie in the back of the van and howl. I cry until Mike comes back out of the water and finds me lying, stupid with tiredness, tear-soaked. The crying helps, a little.

Edward is standing on a vast fallen log, surrounded by trees. Birds trip overhead. Now and then, something rustles. I wedge lighting stands between rocks, the gels dyeing the world turquoise and gold. I think, I can still do this. I can.

A sonographer slides a lubricated wand into me. The machine beeps as she takes stills. ‘The last time, I had sixteen follicles on my right ovary,’ I say. She raises her eyebrows. ‘Well, now you have thirty. At least.’

Dad and Yvonne visit. We go to Werribee Mansion. The sun paints the world in harsh pastels. We walk under a high tree whose branches bear enormous fruit — pendulous and purple-black. It takes us a moment to realise that these are bats, hundreds of them. Every now and then, a squabble emerges, and their strange, veined wings unfold in protest.

March

I drive to Daylesford for a week alone. I intend to write. Instead, when I arrive, something in me tumbles out like fruit from a dropped bag. I am too exhausted to produce. Instead, I read, and I sleep. Once or twice, I do a little yoga. Mostly, I feel shellshocked, flattened with something I cannot name. Something like grief, or shock, or exhaustion. The pressure on my bladder wakes me in the night, crying.

Mike and I pack the van and head to South Australia. We stay with my uncle and aunt, and eat the most delicious roast chicken I’ve ever tasted. We surf beaches we have never seen. We see Mikey and Sarah at Second Valley. We hike to the top of an enormous cliff and gaze out at the sea beyond, and then plunge down to dive into it. The water is clear and shockingly cold. We laugh and play and throw rocks into the water. I am so happy.

A friend calls. A school nearby needs a life model. The art teacher calls me. ‘I’ve never done it before,’ I say. ‘We’re desperate,’ she admits. ‘You’ll be fine.’ I meditate with my eyes open as wide-eyed schoolgirls run charcoal down paper. I feel each droplet of sweat as it sails down my back, my legs. I can smell myself.

We fly to Queensland with Mike’s family. A bus takes us from Cairns to Port Douglas. On Mike’s birthday, we take a boat out to a dive site. I brush over coral, astonished that I am allowed to be so close. I nudge a clam the size of an esky with my flipper, and it slams shut so fast I gasp in water. I turn to see a sea turtle, making its stately way through the water. I swim behind it, enchanted. It is entirely unperturbed by my presence. I might as well be a piece of seaweed. When we meet back at the boat, Mike tells me about swimming with the same turtle. The sea is rough, now. Halfway back to shore, the engine runs out of oil and splutters to a halt. The boat slides sideways down waves. The man in front of me rushes to the side and throws up. His wife follows. Another boat throws us a bottle of oil. We cheer. The staff urge the vomiting couple to sit back down. We slam through water, the bottom of the boat groaning. The engine goes out again. The couple rush to vomit once more. I think of the water between here and land, full of jellyfish and crocodiles. I look over at Mike. His head is back, laughing. When we make it to shore, he is shining, full of joy.

April

Sitting by the lake at Boogie Festival, security guards walk laps of the water, calling out to swimmers, urging them back to land. The swimmers wade in, looking sheepish, then leap back into the water as soon as the guards have passed.

I photograph a friend. Between shots, he wheels away to cough hard, returning breathless. This cold he has is lingering.

In Queenstown. Ian and I drive up Noel’s long driveway. Everyone we’ve spoken to has warned us that he won’t speak to us. ‘He’s got this shed,’ they say. ‘Nobody’s allowed it in.’ When we get out of the car, Noel greets us, handsome and bearded. He shows us the water wheel he’s built from the casing from old street lights. We marvel at it. He grins. ‘Do you want to see my shed?’

Ian cooks while I edit photos and make notes of phone numbers and names. We listen to William Basinski’s Disintegration Loops. At certain moments, Ian lifts a finger, to mark when the sound has begun to fall apart. We sit at the table together and quietly cry.

Joan is 88 years old. She grew up in Linda, just outside Queenstown. It’s a ghost town now. When she was a child, the acid rain in the area had totally denuded the mountain. There wasn’t a single tree or bush. ‘It’s a pity,’ she says, ‘about all these trees. It was much better without them.’ Ian gets a twinkle in his eye. ‘What if,’ he says, ‘we filmed you with an axe, taking out one of those trees?’ Joan grins. The next day, we take her out for a location scout. Every axe stroke lands on the last, perfectly judged. ‘Stop!’, we call. ‘You can’t cut it down til the proper shoot!’

Sarah, Ilana, Phip and I sit outside Fyansford Paper Mill, looking down at the water. Phip cuts slices of cake as she talks about settler conceptions of Australia. ‘They found this country simultaneously weird and boring,’ she says. ‘That’s still with us, I think.’

May

I am shooting at Monash. Each day, nervous students enter the room, and Rockie rigs them in a harness and suspends them in the air. They learn to flip and dive. Some scream as they do it. Others spin until they feel sick. It feels good, to watch each person go from nervous to brave.

My friend calls me. I am just walking onto a train platform. ‘I’ve got bad news’, he says, and I turn around, walking back through the underpass and towards a block of apartments. I sit in the garden there, flanked by flowers, my back against the brick wall holding the post boxes. We talk and we both cry a little. Strangers pass. I am a still point in a turning world.

I go to a writer’s poetry book launch, and watch the hungry way his eyes flick to his partner, throughout. His infatuation is so naked on his face, I am astonished.

Ilana and Sarah and I drink coffee and type frantically, writing text, making lists of names, drawing diagrams. It feels good to plot something grand and foolish again. It feels like being in my twenties, making theatre out of hope and energy instead of money and time.

I see a urogynaecologist. She reaches inside me and winces. ‘No wonder you’re in pain,’ she says. ‘Your pelvic muscles are so, so tight.’ She is funny and full of spunk. The moment I know that the problem is nothing more than tension, the discomfort begins to melt. She scolds me. ‘Just because it’s related to anxiety doesn’t mean it’s not real,’ she says. ‘It is very real.’ She tells me that she has an overactive pelvic floor, too. So do many women in this industry. She tells me how to relax the muscles. I frown, concentrating. ‘Yes,’ she says, ‘Just like that.’

I spend a week installing an enormous text work on the wall at Geelong Gallery. It is long, laborious work, writing straight onto the wall. It is a script, full of gaps. Raking a UV light over the wall reveals hidden text. By the end of the week, I am headachey and exhausted. Mike returns from Apollo Bay feeling the same way. Our covid tests are negative. It is the flu. I haven’t had it since I had swine flu in 2008. Two weeks later, we try to walk the 900 metres to the nearest supermarket. We have to stop twice on the way, gasping for breath. The delicacy of the body.

I photograph The Nightline for Rising. There is a jumpy energy in the air. The artists all turn off their phones and focus on the task at hand. By the time the dress run is over, the lockdown has been announced. The shock is almost a taste in the air.

June

The long nothing-days of lockdown, again. It is not getting easier. It is getting harder.

I get a call from Lisa, the gallery curator. There is a hesitation in her voice. ‘I came back in after two weeks, to check the work,’ she says, ‘and the UV ink is not quite as visible now.’ She is understating it. The ink is gone, absorbed into the MDF or evaporated. A week’s work, gone.

There is only one place in Victoria that has the paper I need to remake the work. When I get it home, I can’t get the lines straight. Mike find me lying on the floor, wailing, having a tantrum like a child. When I finally gather the energy to return to the work, I realise the problem: the paper roll is cut wonky. When it is installed, I come in one day and watch people engaging with it, the way one woman calls out to another, ‘Oh my god, look! Look, there’s hidden writing!’

We have tea with Magda and Ivan, which becomes lunch, which becomes drinks and then tea again. The joy of new company, of learning new people, of good food and laughter.

The night before a big shoot, I topple into bed and rub an itch on my eye. Ten minutes later, I pad into the bathroom to find an antihistamine. When I turn on the light, my eye is some horror-thing, swollen so much I can’t see out of it. I start shaking. Mike drives me to hospital. The triage nurse is bored and affectless. He watches me quaking and raises an eyebrow. ‘It happens sometimes when I’m stressed,’ I stammer out. He looks incredulous, then offers a tiny gesture of kindness: ‘You’re in the right place. You’ll be okay here.’ Four hours of waiting later, the swelling has gone down a little. I leave and fall into brief sleep.

Mike and I go to a Monster Truck rally with Luke. I spend the whole time with my hands over my ears and my mouth open in a dumb expression of delighted shock. It is an experience of total, sublime noise and spectacle. A rodeo clown rides a lawnmower fitted with a jet engine. Fire streaks out behind it. I am half-laughing, half-yelling. We win soft toys at a pop gun stand. I am thrilled.

July

We watch Poltergeist in a brewery in Torquay. The movie is silly, but my body seizes up in response to it. I have no skin between me and the world at the moment. Other people’s fear floods me. Even daft, filmic fear. I have no guard against it.

Mike and I fly to Queenstown, to shoot the video components for Colosseum with Ian and Rosie. It is a dream week, full of sun and visions that sound like dreams: a motorbike glowing bright against mountains; girls lighting flares on the burnt carcass of a car; fire truck hoses and SES daymakers bearing down on exhausted football players, their hair wrapped wet around their cheeks. Mike is everywhere just before I need him, nimble, essential. Joan cuts right through the tree, dressed in a spangled jacket and ball gown. It is good, oh, it is good.

I have my first skateboarding lesson. Al, the teacher, shows me and another woman how to fall onto our knees, first on the flat, then on concrete and wooden ramps. Finally, he has us fall into the mega ramp, seven metres high. When we are both down, laughing, half-terrified, he looks impressed. ‘Nobody ever does that ramp on the first lesson. You two are the first.’

I buy a butter dish. I am more delighted with this purchase than nearly anything I have ever bought. Every time I use it, I am simply and wonderfully happy.

August

My book is released. Mike and I have dinner with Luc and Jess: good wine, and food, and pride. Jess sits on Luc’s shoulders to peer into the Readings window. ‘I can see it!,’ she yells. ‘There it is!’

I head into Abbotsford for a development with Katerina. Four of us sit and think and weave together. The news comes in fast and hard. An 8 pm lockdown. Tamara, Zoe and I scramble to catch trains. We bump out fast, the development in tatters. My launch is meant to be in two day’s time. I walk into the kitchen next to the hall and allow myself thirty seconds of fast, hot tears, before I come back out to help roll rope and stack chairs.

I do headshots for a high school girl in her backyard. For the first time, even regional work feels fraught, dangerous. I wear a mask and back away when her mother comes near to tell me some story about her child. The mother looks at the girl. ‘It’s a pity about her fat face,’ she says to me.

I do a series of radio interviews about the book. Before one, I drink too much coffee. When the woman asks about my mother’s death, I walk in fast circles around my office. I have no idea what I am saying. I am wondering if I am about to throw up or pass out. Later, my publisher emails me. ‘You sounded so relaxed and calm on that one!’ she says.

September

Daniel messages me while reading my book. ‘You were always your chronicler,’ he writes, ‘the one amongst us best able to document what we did. I just wanted to say thank you, that you are superb, that the world is at its most dazzling seen through your eyes, whether those eyes be a lens or a sentence or your own.’

We go to the Warrnambool Hot Springs with Pen and Jason, then have dinner at a pub. It is wonderful, glorious, the world almost painfully detailed. Melbourne is still locked down. The guilt of that.

I have my second vaccine. I am terrified of side effects. There are so few: a little fatigue, like a gentle hangover. A hard lump in my armpit that subsides after a few days. A little bubble of hope, of calm, of control.

Lisa and I sit in the park like teenagers, drinking wine and eating gnocchi. We talk about love and art and Geelong and the things that brought us here. I walk home, swerving a little, full of joy.

Dad is hospitalised with pneumonia. Days of nervous phone calls follow. When he is released, I go to visit. I wake in the night, hot and sweating. I am convinced I am sick, that I have made him sick. Even after a test confirms that I am well, I am so stressed that I start having episodes of protracted déjà vu, crawling skin and the strange sense that I have just woken from a dream. This is not sustainable. I do not know how to process this fear.

October

I pick up a box of lemons from a man on Reddit, exchanging them for a bag of cashews. Later, I notice him making posts about refusing to get the booster vaccine, and it is strange, the collision of the slightly shy man whose lemons I have preserved and the flat, annoyed voice on the computer screen.

I take part in a writer’s festival event. Nobody knows who is meant to be leading the session. ‘Just talk about whatever you think!’, we’re told. The other two writers work in domestic violence and tricky cultural settings. I feel sick with dread. When we log on, one of the writers offers to facilitate. ‘I do it for a living,’ she says, ‘I know what to do.’ With her leadership, the session is a success. I’m so grateful I could kiss her through my screen.

Tasmania won’t let us into the state to install Colosseum. Martyn, Ian and I zoom in for the showing of the work for the people involved. Rosie hosts magnificently from the RSL. The response is joyous; we are proud and relieved. Three days later, the work is installed: a huge seating bank, tonnes of gravel from the footy pitch, a powerful projector and speakers. We are all on WhatsApp when the call comes. A covid-positive man has snuck out of Tasmanian hotel quarantine. The festival is shutting down on its opening day. The town is shocked. Rosie sends us photos and stories of teary locals. Joan drinks champagne for thirteen hours with Rosie and still manages to walk home.

I book into several events for Liveworks. I don’t attend a single one. I can’t do any more Zoom events. I just can’t.

Ben gives his third milestone PhD presentation online. He has created an extraordinary video in lieu of the usual 20 minutes of nervous talking most people provide. Even through the screen, I can feel how impressed the assessors are. I am so proud.

I call David and Rebecca and tell them that I’m not sure what this new book I’m working on is, that I’m lost in the weeds. A month later, the draft manuscript is done. I have found the way through. The way is through work. It is always the case, in the end. I am proud of what I have made. It is fiction, a series of shorts, interspersed with metatext. It is called ‘The Part Where We Panic.’ It is about apocalypses and endings and ethics and how we think about our world. It is good, I think.

November

The online event for the award I won for the book is plagued with tech issues. I sit quietly on Zoom for an hour, waiting for someone to introduce me to the panelists I’ll be having a conversation with. Nobody does. We go live suddenly. The sound is so bad that nobody I know stays online for more than ten minutes; they just can’t hear. When it ends, I am very tired.

I visit Luc and Jess. They are both knackered. I have a beautiful, long hug with each of them, lying on floors and beds, full of love.

I go to the doctor. I tell her I am exhausted. She nods. ‘Everyone is exhausted right now. I’m sorry. It’s probably not you. It’s everything.’

Eve has her birthday at the Retreat hotel. It is a night full of old friends holding each other with tenderness and grace, laughing at our inability to conduct ourselves socially, telling each other that we love each other. It is very special.

After years of rescheduling, David and Jordan and I shoot the promo images for David’s new show. He stands on a paddle board in a clay lake at nightfall, holding a flare. There is a rush of sound as the flare lights up, smoke to the heavens.

I visit Jimmy at his apartment. It is high, high up. The glass railing on the balcony is so low. I reel away from the edge, vertiginous and frightened. He shows me his French butter dish, the way it holds the butter in water. Being an adult seems to disproportionately involve getting excited about good butter storage.

I stay at Jordan’s. After dinner, when the house is dark and quiet, we open our laptops and write. We swap words and listen to each other read, the little hums of assent and wonder and laughter at each other’s writing. It is good to write in company. The breaking of the solitude.

I am in a development. I make an idiot of myself, offending someone I deeply respect because I can’t stop talking. I try to pull myself together, but then suddenly there is a positive rapid antigen test, and then a positive PCR and it all shuts down. I call Mike and he picks me up and we drive home in sad, tired silence. A week later, when my second negative test comes in, we’re both astonished. We marvel at the vaccine.

Mike finishes reading my new book. We lie in bed together and workshop the last line. I submit it to my publisher. Now I will wait.

December

Mike finishes full time work. He has received funding to create his own web series. I listen to him on a pitch meeting with a big network, the laughter in the room. It feels like he is on the right path.

A man I’ve worked with a few times has died, and surrounding his death is the uncovering of terrible truths. It is a curious thing, to hold respect and horror together.

Dad and Yvonne come to visit. I do rapid tests every morning, and a PCR when they’re gone. While they are there, there is a beautiful calm, a joy. We go to the gallery and eat good food. I love seeing them. Every time feels like a gamble, though. Love and fear.

Five of us sit on the side of the road, dropping liquid into our rapid tests, watching the colour change as it rises over the markers. A bus pulls in and the driver laughs at the sight. It is hot in the sun, and we are all jangly with nerves, so close to Christmas, so desperate not to get sick.

I have lunch with Jordan. On the way, we get coffee. I have a panic attack at the restaurant, and have to stagger outside to sit in the alley, trying to breathe, feeling sick and overwhelmed and horrified. That night, my dad calls me when I’m shooting an event. ‘Let’s not do Christmas in person this year, hey?’, he says. ‘I don’t think you’ll enjoy it if you’re just scared about making me sick the whole time. It’s just a day.’ I sit on a stack of chairs and sob with gratitude and despair.

Christmas with Mike’s family is rowdy and boisterous and beautiful. On Christmas morning, Mike and I listen to ‘White Wine in the Sun’ and cry. I listen to a Zoom Christmas service from a local church and sob so hard it hurts. The words and the songs are words and songs that once meant family and my mother and my grandmother. Now, they mean a different world.

Danny and I sit in a hammock at Luc and Jess’ and watch the light through trees overhead. There is wind, and birdsong, and no other sound. It is hot, and beautiful, and calm. I can feel myself recovering something that has been missing. I’m not sure what it is just yet.

S x