2018

Countries visited: 1

States visited: 3

Plane flights: 6

Most-liked photo on Facebook: this one, of Eve and I accidentally wearing the exact same outfit in Tasmania.

People who made me cry: none, as far as I can recall.

People I made cry: two, to the best of my knowledge.

Men who I held in my arms and told that everything would be okay: 3

Lost Thornbury dogs returned to their homes: 8

Most consecutive days on which I meditated: 32

Favourite moment that I photographed: Jordan’s perfectly placed head tilt at the NGV.

Time I was most stressed: 6 pm on the night of the RMIT Art Auction.

Favourite film: ‘Ema Nudar Umanu.’

Most-played album: a mix CD from Jordan that lives in my car.

Most played songs: ‘Water Fountain’ by Tune-Yards, ‘The King of Spain’ by The Tallest Man on Earth.

Song I most often had stuck in my head: ‘Jackie’ by B.Z. feat. Joanne. (We sing it to the dog).

Favourite TV series: I only watched one show, which was ‘Inkmaster’, and I loved every single trashy second.

Number of books read: 29

Of which, the best: ‘Her Body and Other Parties’ by Carmen Maria Machado.

Best articles I read: ‘The Dramaturgy of Queer‘ with Jean Tong interviewing Bridget Balodis and Rachel Perks for Witness, talking about tearing down the patriarchal structures of the well-made play and the rational rehearsal process; ‘Whale Fall‘ by Rebecca Giggs.

Best gig I saw: Emel Mathlouthi performing as the sun went down at MONA FOMA.

Best piece of theatre I saw: Western Edge Youth Arts’ three productions – ‘Antigone’, ‘Lele, Butterfly’ and ‘Grace for Race,’ all featuring the most incredible, passionate, talented and immediate performances by young actors who reinvigorated my belief in the power of the performing arts.

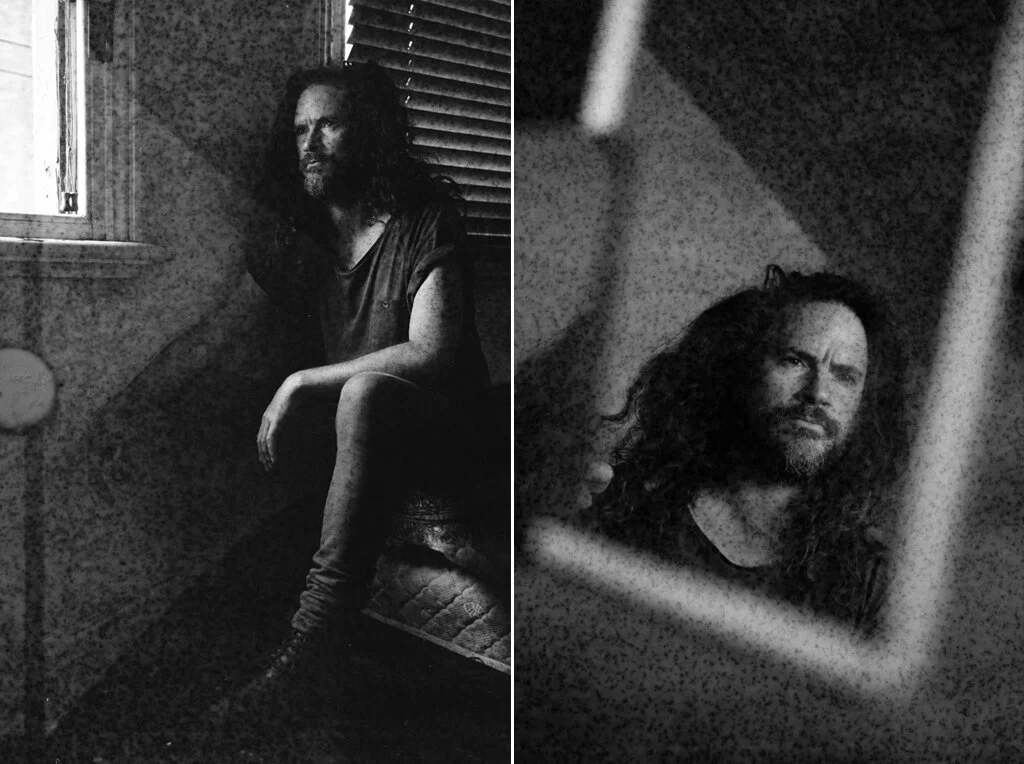

Shows I most enjoyed shooting: ‘Apokalypsis’ and ‘Moral Panic’, if trying not to sob while photographing for a whole act is any indicator of enjoyment.

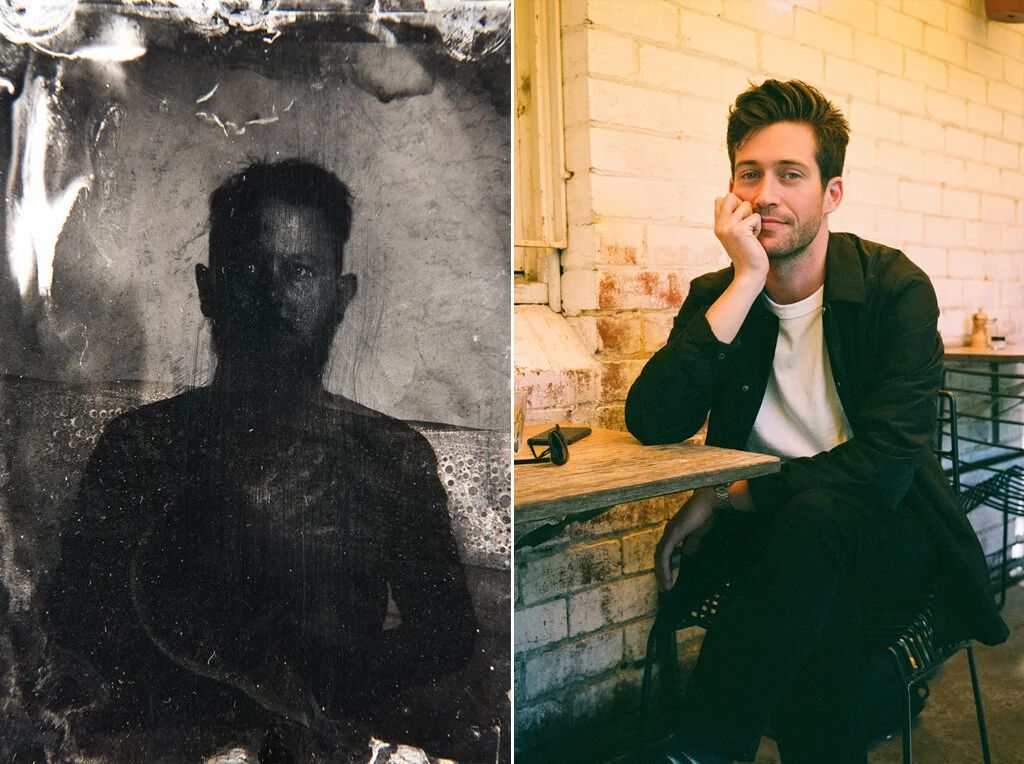

Favourite image I shot for work: This one, for MUST’s production of ‘After Hero.’

Shoots that went really terribly: 1

Favourite things I made: ‘Seep‘, an audio tour of Brunswick RMIT, set in a future where Melbourne has been flooded as a result of climate change, and ‘END FM‘, a receipt printer that prints a transcript of a commercial radio station text line as the apocalypse happens.

Artists I grew to especially love: Ilya and Emilia Kabakov, Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Elín Hansdóttir.

Artist I grew to especially loathe: John Duncan, Vito Acconci.

Best decision: doing an MFA.

Decisions I regret: none.

People who told me they wanted to die: none.

Best date: A hike and a picnic at Werribee Gorge.

Best $10 purchase: a plastic daily pill organiser.

Best piece of practical knowledge gained: if you lift up a lawnmower while yanking the pull cord, it starts much faster than if you leave it on the ground.

Titles of lists I made:

The Mary Celeste

Bring in

To do

Things I Never Thought I’d Let Happen

13 Ways of Looking at a Blackbird

Here is a list of some interesting people from everyone’s dinner parties

Workshops today

Who broaches the threshold?

What to focus on?

Next 3-4 months

Breakdown

Holiday works

Grand narratives

Art website

NAOSHIMA

Narratives for Viewmaster

Look up / address further

Solstice

Arduino

Projects

Rituals

Multifunction Polis 2020

KABAKOV

Test Sites

Mythology

Whale

Time

Climate

Hidden spaces

Sounds

TODAY

Moleskine notebooks filled: 5

Words and phrases I double underlined in notebooks:

Is it always night here?

Ask ‘What is sex?’

Jill Soloway video

The flaneur is inherently masculine

Process, not outcome

Shoeboxes

Anxiety

Caval Card

Re-articulate

Tragi-comedy

Filibuster v filibuster

Spatialise time

Ectoplasm earrings

Threshold

Creepy

Penumbra

Making an emotional/turbulent experience felt, literally and physically impactful.

Opening the secret door – becoming special.

Hierarchy

They don’t have to sit next to each other.

MATERIAL AT ITS END

Missing the quiddity.

Walk with my footsteps

The lift

It makes sense that there’d be 13.

Narrative as closure

Tedium/banality

Evoke cf illustrate

‘The man who flew into space from his apartment.’

Spontaneous combustion chair

Depth

Portals

The space becoming implicated/complicit

Books chewed by dog: 3

Of which, library books: 1

Instances of accidental mid-photoshoot arson: 1 (of course, someone happened to be filming with a drone).

Shittiest day: The day before I was hospitalised for appendicitis and blood poisoning, moving through a fog of pain and exhaustion, the sofa cushions too colourful, sleep too shallow.

Day that felt most golden: two days out of hospital post-appendix surgery, lying in the backyard in the sun with my feet on the wall, feeling my body fixing itself, realising with sudden clarity that I was enormously lucky to be living the life that I lead.

Moments I felt so happy I could burst: any number of soft, sunny Sunday mornings, curled in bed with Greaney and the dog, marvelling at what it is to love and be loved.

Wisest thing anyone said to me: Sruthi Kathic, over beers after the MFA Art Auction –

“Putting labels on yourself and the things in your life forces you to become a hypocrite. Everything is constantly in flux. You are constantly in flux. If you stop defining yourself and just allow yourself to exist, you realise that you change minute by minute.”

Last year’s new year’s resolutions:

Put down your phone.

Spend more time staring into space.

This year’s new year’s resolutions:

Be softer, be kinder, be slower.

Defining word for 2019: depth.

Moments that stand out:

January

New Year’s. Midnight. I lie on carpet in Cundare with Greaney and Luc and Jess. Jess is pregnant, fighting nausea. We play Shithead, laughing. The clocks ticks over to midnight. We hug each other, kiss. At five minutes past, we go to bed, smiling.

We are driving home from Fitzroy, with a giant black greyhound in the car. Greaney sits with him in the back seat, points out the window. ‘See that, Jacko?’ he says. ‘That’s the world. We’re going to protect you from that.’ Later, with the dog’s head resting on his thigh, he tears up. ‘I’m so happy,’ he says. ‘I love him so much.’

The dog makes a strange noise when he lies down. At first, I think he is growling. We realise that he just makes old man sounds when settling. As soon as our alarms go off in the morning, he jumps onto the bed, forces a gap between us, flops down, breathes out and dozes as we scratch his ears.

At the airport, I realise that I have forgotten to take my pocket knife off my keys. I unhitch it from the keyring and walk into the newsagent. I slip it behind a crossword magazine.

In Hobart, Eve and Mikey and I wade waist-deep in cold, shockingly blue water. We stare out at the ocean from giant stone boulders. Two days later, Emel Mathlouthi conjures devastating magic as she sings, the sun setting behind her at MONA. As the last fragments of song fade on the wind, the pea-hens who live on-site start up honking. The audience laughs, and the sound flutters out to sea.

Back home, in the airport newsagent, I reach behind the crossword magazine. The knife is still there. I pocket it quietly and leave.

February

Mikey and I direct a music video for Baby Blue, making a mess, creating something silly and sweet.

It is the first day of my MFA. I am terrified. The third semester students give presentations about their first year’s work. I think, I will never be able to speak that clearly and critically about my own making. I think, I am scared that I have nothing to say. In the break, Te’ Claire and I talk to Rowand about his practice. I am so nervous that I am shaking. I breathe in the toilets and think, I just had a conversation about art with an artist and I didn’t make a total idiot of myself. I think, I am where I have always wanted to be.

Sally, my supervisor, asks me when I can meet her to talk. I presume this will happen in a few weeks, once I’ve sorted my head out. She laughs. ‘How’s today?’ She teases out the faltering threads of my thinking and hitches them to seams to follow.

March

I carve rings out of wax, and then shape them once they’re cast in silver and gold. I make my own 30th birthday present, and make Greaney and I matching rings. This is the true alchemy, taking a roughly cast thing and shaping it into something beautiful.

To my great surprise, I do my first invert in a pole dancing class. I feel strong, hanging by my thighs, hands off the pole.

I hear Kate Just talk. She speaks about how women so often portray their bodies in art as a site of trauma. She talks about making work that complicates the body, that makes it a space of love, not just pain.

Greaney and I swim through the City Baths, wearing little islands on our heads. A woman I know sees a man we both know, and says, ‘I will not swim with him. I refuse.’ I know what it is to be complicit.

I photograph two friends having sex in a room where someone once threatened to ruin my career because of who I’d fucked. The strange ways in which the world becomes not so much circular as snakelike. The three of us are smiling in the morning sun.

It is Greaney’s birthday. We do an escape room called Deep Space. In the last few minutes, I am terrified, exhilarated, frantic. I wish all art could do this. When we leave, the woman running the space looks impressed. ‘Most people don’t survive,’ she says.

I attend a workshop titled ‘Fundamentals of Rope Bondage’ as research for a show. We are bad attendees, giggling at everything, sneaking looks at the couples and the soon-to-be-lovers leaning into each other, eyes half-closed. When I am being untied, the knots make the ropes thrum, and I understand.

I read ‘The Hour of Our Death’ by Philippe Ariès, and the semester slides into place like a jigsaw.

April

It is my 30th birthday. I am surrounded by people I love, eating food that is almost too good, feeling the particular anxiety of being with too many wonderful people at once, of not being able to talk to them all, of being so full of love.

I have my first crit. I spool rolls of receipt paper, handwritten with jumbled fragments of text messages from a time before death came to me and the people I love. Steven says, ‘You’ve made a threshold in the space,’ and a light goes on in my head.

Geraldine Quinn is telling us about how her dog saved her life, and the work has such tenderness and softness. She tentatively rollerskates around the audience, and she is proud and I am proud and we are all proud together. Later, Betty Grumble yips and dances and roars and the women in the audience are one creature, fired up and ready for revolution.

I am sitting around a campfire at Lake Condah Mission, surrounded by artists, thinkers, makers. I say that having someone ask to collaborate with me, instead of asking if I could capture their own work, was deeply meaningful, deeply validating. Without realising it, I am crying. Two days later, Rajni is speaking, soft and grave and authoritative, and something in me cracks open and the tremulous husk of judgement in me falls away and kindness rushes in.

Rebecca and I are topless, black-skirted, tied to a tree with bright pink rope, breathing, watching the sun go down. Droning and drumming and whispering rustle across the lake bed. Suddenly, the clouds part and we are drowning in light.

May

I pick up a coffin from Spotswood for a shoot, but am struck down with food poisoning on the shoot date (spoiler alert: it’s not food poisoning, it’s my appendix). The next day, still shaky, I put Greaney in it and drive him around in the back of my people mover, an unlikely hearse. We talk about death. I ask which funeral song he’d like to hear. He chooses Israel Kamakawiwoʻole’s cover of ‘Over the Rainbow’, and we drive through the neon lights of the night and he cries.

Fleur, Kieran and I have a meeting with a podcast producer about representing Contact Mic. For a few weeks, we are excited, dreaming of narrating ads for Squarespace and mattress brands. Later, we have a meeting. We do not sign up to the network. We decide that the next episode will be our last.

I am doing a promo shoot along Merri Creek. A cyclist has pulled up, asked to document the shoot with his drone. Fine, we say. The model lights a smoke emitter. She sets it down on the grass. Flames erupt beside her. We try to stamp them out, but they spread so fast. Minutes later, the whole hillside is on fire. By the time the fire brigade arrives, several trees have started to burn. We watch quietly, along with various cyclists, parents and onlookers. When the blaze is out, we present ourselves to the fire fighters, ready to be arrested or fined. They ask how the fire started. I give them a smoke emitter. ‘This is great!’ on says. ‘You’ve saved us so much time in figuring out what got it going.’ I linger, awkwardly. ‘Do you need our names? Our details?’ ‘No, no,’ he laughs. ‘It was clearly an accident. Off you go.’ We leave, confused, relieved. The next day, I get an email. The cyclist has set the whole incident to music, posted it online. I ask him to take it down. He is miffed.

I photograph ‘Apokalypsis’ for Next Wave, and leave feeling like I want to cry and run and write all at once.

I fly out to Sydney to see the opening of ‘Blackie Blackie Brown.’ I hold Greaney’s hand, feel it tighten on the cues he’s nervous about. We drink wine overlooking the wharf, and I am so proud of him, after the months and months of sixteen-hour work days, with no breaks and no weekends. Nakkiah Lui makes a speech. She thanks the cast, the director, the designers, the stage managers, the operators, the staff at the STC. She mentions everyone on the project except Greaney. In the hotel room, street lights filter across the bed and I can see his face in the dark.

Greaney and I attend a Ronnie van Hout talk at ACCA. He gives a rambling presentation about aliens, goes half an hour overtime. I am enchanted. I think, I am going to make work about ghosts.

Prue gives a presentation at RMIT, about artwork as activism, about how disability arts are excluded from mainstream arts. She is fierce and funny and nobody stops talking about it for weeks.

I photograph a Green’s feminist salon. Sex workers are protesting outside. The women speaking at the salon talk about porn and sex work in a way that makes me feel sick. Their words are patronising, paternalistic. I feel deeply uncomfortable. I take photos, holding my breath to keep the shots steady.

June

Greaney and I arrive at the Gold Coast airport for our flight to Japan. I have had 30 minutes sleep, and am hungover with exhaustion. We find out that our flight has been delayed by a day. They send us to a hotel. I collapse into the soft, white bed with a gratitude that nearly hurts. Later, we sit with our feet in the pool in the twilight and talk softly with other travellers. When we finally arrive in Tokyo, I am rested and ready.

We catch the ferry to Naoshima, and ride electric bikes up island hills. I am so excited I could explode, jumping up and down on the spot with joy. There is art everywhere. That night, footsore and sunburnt, I sit in an onsen surrounded by Japanese women. The tiled floor beneath us has erotic illustrations set into it. Without my glasses, everything is foggy and soft, bodies and breath and heat.

We walk through the forest on Teshima. The air is full of the thick scent of pear blossom, smelling like semen. We pass nobody on the road, except for a black snake that skates across our path. We step over the gate announcing Christian Boltanski’s artwork. We walk uncertainly through the trees. ‘Stop,’ Greaney says, ‘listen.’ The forest is full of the sound of bells. We come to a clearing and see them, every clapper inscribed with a name. The rustle of leaves precedes the bells. I think, spirits move in these hills.

In Kyoto, we wake up one morning to the room shaking. It feels different to what I would have expected an earthquake to feel like. Slower, somehow. Wider. More fluid. Greaney’s first thought is ‘What did I do wrong?’ Mine is ‘But I’m not wearing pants.’ The shaking subsides. The gas has gone out. Everything is very quiet. A few seconds later, the sirens begin.

I interview people about ghosts. Stories of visitations and apparitions and visions and dark things pushing people down into their beds and bathtubs full of blood and a certain deep knowing. I get goosebumps every time. I start talking to my house when I am alone at night. I say, ‘If you’re there, I don’t want to know. We’re looking after this house. Go to the light. Please, if you’re here, I don’t mind, I just don’t want to know.’

July

It is twelve degrees outside and I am lying naked on the roof of a carpark with hundreds of other people, modelling for Spencer Tunick. Spencer’s assistants run through the crowd as he screams over a megaphone at them, giving bad directions, demanding things they can’t possibly do. He is aggressive, neurotic. Afterwards, people laugh and twirl in the morning sun. ‘I love his work,’ they say, ‘and this made me feel so good about my body.’ I think, if I treated my models and staff the way he does, nobody would ever work with me again.

I am judging a local photographic club’s monthly photo competition. I give feedback to one man, who scoffs at me, talks back, sneers at the notes I give him. In my presentation, I talk about being hung in the National Portrait Gallery. He is still sneering.

I photograph a cabaret performer in a dark theatre, painting light across his face. He falls asleep mid-shot. I am worried about him.

I attend a post-show discussion through Witness. A woman is talking about how mental illness allows people to see the truth of the world, that it is a necessary and beautiful thing, that depression is actually a state to be desired. The table goes tense. Someone mutters something about their suicidality not being up for romanticising. There is a sharing of looks, of understanding, of the camaraderie of suffering.

August

Jesper sends me the most beautiful, concise piece of code and I suddenly understand why people say that good coding is like poetry. I install a receipt printer in the Burrow, and it spits out a script for a radio text line during the apocalypse. People kneel to read it, as the paper piles up and up.

Luc has taken to starting phone conversations with ‘Jess hasn’t had the baby yet.’ Until one day, she has had the baby, and my dear friends have a daughter, and she’s tiny and her hiccups take up her whole body. Her cheeks are so soft they feel like smoke machine haze.

Greaney meets his niece and discovers a sudden, giant love that he never knew was there. I photograph her and she does giant, oversized farts. I am doubled over laughing.

I stand on Russell Street with a friend, saying ‘Oh my god. Oh fuck. Oh my god’ as cars grumble at the lights. Panic ripples through the air like a searchlight.

Mum and I stand looking at one of Felix Gonzalez-Torres’ light strings at the MOMA exhibition at the NGV. I tell her about the work, about how eventually, all of the globes will burn out, about how frightening it must have felt, being gay in America in the 80s, watching the people you loved die of AIDS. We both tear up, a little, looking at those lights, all lit, all waiting to die.

The MFA Art Auction has just ended. I have lost my voice. I am sitting in Gemma’s studio, crammed with people. Someone passes me a beer. Someone else says that we have raised $10,000. I am swimming with tiredness and pride and love for these people.

I do a sound walk at the CCP. A group of us walk thoughtfully through the streets of Fitzroy, frowning. A carpark buzzes alarmingly. A jackhammer is almost too much. The sound of a man taping a poster to a wall is nearly erotically pleasurable, the taut pull of the tape, the tear.

September

It is Jordan’s birthday. We climb the netting at the back of the NGV, talk about how quickly things change, how suddenly we find ourselves on the brink of something big.

I am scrolling through a Twitter thread. An American girl is newly out as trans, has tweeted about having no idea how to dress as a woman. I contact her, post her two of my old dresses, both worn to weddings, both imbued with the smell of cardamom.

A few weeks later, she posts a tweet.

‘CW: Suicide

I nearly just killed myself tonight. I put a gun up to my chin but couldn’t pull the trigger. I was so close. All my pain could’ve gone away in that one moment. I must really enjoy suffering since I’m still here.’

I stare at the screen and think about distances, and how the internet makes them small and vast, all at once.

I am at Geraldine’s house, wearing a giant inflatable red costume, trying to sit down without the air bursting out around my face. I waddle away from her. She bursts out laughing and then I do too, cocooned in red polyester and fanned air.

I get home at 1 am from a shoot. I sit on the edge of the bed. I notice that I am not physically tired. This year, I am learning the difference between physical exhaustion and psychic exhaustion, a sort of tiredness-in-the-soul.

I am modelling for a local brand, on the other side of the camera for once. The man taking the photos is talking about his first fashion show, the older woman he hired as a model, how he wanted to fuck her. He tells me that my ass is my best asset. He tells me this several times.

At Ben Landau’s ‘Retreat’ at the Mechanic’s Institute, a group of us lie with our heads together, humming, feeling the vibrations through our skulls. A woman, a stranger, looks over. I beckon her to join us and watch relief and pleasure crash across her face like waves on rocks. The way that small things are also large.

In a crit at RMIT, Steven looks at the giant frames I have installed on facing walls in the Gossard. ‘The idea of bringing together Mapplethorpe and Malevich,’ he says, ‘is approaching genius.’ He’s joking, but I write it down anyway.

Sarah is DMing a game of DnD, playing the mayor of a cursed town, dancing frantically to divert attention from the terrible void in the town square. I am laughing at her, and as I laugh, she dances harder, and I laugh more, until I can barely breathe.

At Cundare, Kieran is giving me tips on using Reaper to finish my sound walk. Fleur is reading us excerpts from a book about whales. The particular pleasure of creative company.

October

I test run my sound walk. The binaural audio when Jordan’s voice, frantic, is in the campus phone booth, is so precisely situated that it is uncanny. It is almost impossible to believe that there is not a person in there. I watch Sophie and Christina’s faces as they stare in disbelief at the empty booth.

I am painting a wall at RMIT Brunswick, installing the physical components of the sound walk. I am extremely tired. My stomach hurts. I think, this food poisoning has really knocked me around. I need to sit down. I drowse on a patch of grass near my car. Later, I am lying in bed when I start shaking, big, strange shakes that I can’t control. Greaney comes in, holding a plate of toast, a fried egg on top. The toast goes cold as I hug a wheat pack and we call the Nurse on Call. I sit in the ER waiting room at the Austin, grumpy that nobody will let me drink water. ‘I have a cold,’ I say. ‘A cold and food poisoning. I’m fine.’ The next day, as I emerge from the fog of anaesthetic, someone in a mask tells me that my appendix had partly died. The day after, six doctors tell me I have blood poisoning. ‘But I feel fine,’ I say. ‘Really, I feel fine.’ Artland opens while I am in surgery, dreaming of nothing, drowning in black.

Eve and I take a slow walk around the block, me unsteady and aching, bruises flowered across my stomach. A group of young boys are selling homemade lemonade and lollies. One of them performs a magic trick for us. We give them ten dollars and watch their eyes nearly fall out of their sockets. They give us bouncy balls shaped like eyeballs.

I shoot ‘Fire Gardens’ for Melbourne Festival. Eve and Greaney stand on a hill, surrounded by sparks as the fire leaps into the windy air. It looks like the end of the world. People try to take photos on their phone, give up and just stare.

I give my end-of-year presentation at RMIT. I think back to the start of the year, and am amazed by the clarity with which I can discuss my own practice. Jan pokes her head into my studio. ‘That was really inspiring’, she says. I am dumbstruck.

Greaney and I clean dishes in hazy morning sunlight, singing Regina Spektor’s ‘Uh-Merica’ in the style of Tom Waits. Laughter punctuates the lyrics like bubbles in water.

I read Carmen Maria Machado’s ‘Her Body & Other Parties’ in bed. That night, I toss in half-dreams, filled with sex and horror. I wake with a spider bite directly in the middle of my sternum.

November

I am playing D&D with Sarah, Han, Greaney and Luc. Greaney is improvising an inspirational rap over trap beats. Luc and Han, who have just met, lock eyes, and start flexing their pecs together in time with the music.

I am walking down Errol Street as the sun sets. I give ten dollars to a man named Zack sitting outside the IGA. ‘You’re a sweetheart! God bless you!’’ he calls after me. The gold of the sun hits the festoons strung outside the Lithuanian Club. Everything seems too colourful, too beautiful, too soft and bright. I am so full of the world it aches.

I am shooting ‘Moral Panic.’ Kai is saying, ‘You’re incredible’ and I am crying. Jen is touching Kai’s face, saying ‘Yes, but so are you,’ and I am crying. Jen is saying ‘we will not be killed any more’ and I am crying. Jen is summoning all the rage and fear and hope and fury and sex and kindness and community and humanity and I am crying. I am trying to shoot and I am crying.

I am on the roof of building 100 at RMIT with Ben. We have jumpers tied around our eyes, blindfolded. We are talking about our most vivid memories in the dark. I have forgotten that I cannot see. We have been talking for half an hour, or an hour, or ninety minutes. Time is gone. We pull off the jumpers and blink, blinded in the sun.

December

My dentist is looking at my worn down gums, the scars crossing my cheeks from where I chew them. ‘You have to be kinder to yourself,’ she says.

In Castlemaine, in a hot room lit with lamplight, I sit cross-legged on a bed next to a sleeping baby and watch her breathe. Between breaths, I am terrified, until the next one lifts her chest, impossibly small. Her arms are up like she has run a marathon.

I am at Lerderderg Gorge with Jordan. We are perched halfway up a rock wall, motionless as lizards, drying in the sun. As we leave, a group of men come to the dam, climb the rocks and jump into the water. I hold my breath every time one of them jumps, don’t let it go until he pops back up above the water.

Greaney and I arrive at Luc and Jess’ place. Jess opens the door, covered in red. We follow her to the bathroom, where the whole room is splattered with exploded tomato sauce. She is laughing so hard she’s almost crying.

The summer solstice. Candles, whiskey, a spell. I wake up in the night, shaking all over. The next night, I wake up to the sound of sirens. A house a few doors down is spewing out flames and smoke. I stand with the neighbours on the cold street, watching it burn. A woman called Chris, wearing a pink chenille dressing gown, dabs her eyes. I hug her. The street is painted blue and red from the fire engine lights.

I am sitting, collating readings for uni, cataloguing artists. I am watching Greaney play The Witcher, commenting occasionally. I am arrested by a simple, profound joy. I am deeply, suddenly happy.

*

S x